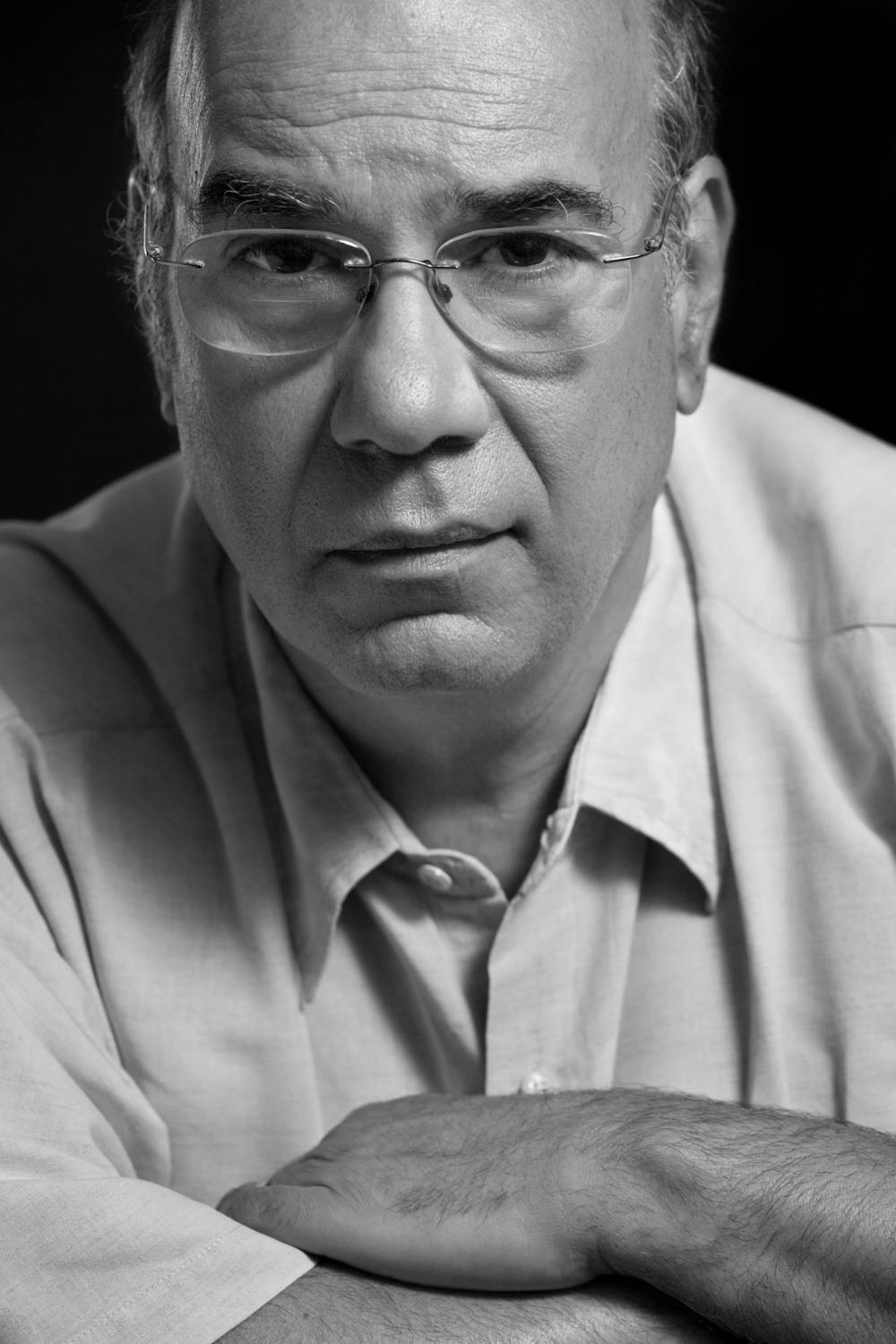

To commemorate Jay Parini’s retirement from his position as professor emeritus of English and Creative Writing, some of the Arts & Culture team sat down with him to chat about his career, life post-retirement and everything in between.

Ellie Trinkle: Why don’t you tell us about yourself. What have you been up to in the past few weeks?

Jay Parini: This is my first semester not teaching in 50 years. So, I’m really enjoying my new lease on life in my new position, which is Writer in Residence at the college. I keep my office and I’m still talking to students and supervising theses and trying to be an active member of the literary community on the campus and to be here for people.

My mornings are always devoted to writing, and they have been for half a century. I write every morning, often in the Haymaker Buns Coffee Shop. Then I go home, write some more and play basketball or swim.

I’ve got a novel I’m finishing about Graham Greene, the English writer, whom I met some decades ago; I have a book of poems that’s almost done, and I just finished a play. In another recent book for the Library of America, I chose from some of my favorite poems from the Puritans to the present, with an essay on each one.

Anthony Cinquina: I want to ask you about the variety of kinds of writings you’ve engaged in. It seems to me that you’ve managed to strike a good balance between different forms of expression. There’s memoirs and biographies and novels, and you’ve been involved in films and plays now and poetry, of course. Do you find that you’ve balanced it well, how have you done that?

JP: I think I’ve been naturally inclined to write in different forms. When I first began writing, I thought “I’ll just be a poet.” And then, I started finding myself writing longer and longer poems. I thought “Well I must try this as a piece of fiction,” and I started writing novels. And then, as a fairly young man, I got involved in writing biographies. Once I wrote one biography I liked doing it, so I wrote six biographies. I’ve written biographies of Robert Frost, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Gore Vidal and Jesus.

Memoir is a more recent genre for me. I had great fun writing “Borges and Me” — my memoir of my travels in 1971 with the great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. He and I travelled together in the Highlands when I was 22 and he was in his 70s in my old car. He was totally blind and wildly talkative.

I’ve also been involved in filmmaking. One thing led to another, and I’ve managed to do three movies, and not do about 10 movies. That’s because projects often fall through.

Christy Liang: How do you see all these mediums as different, or perhaps ultimately similar, vehicles of truth?

JP: It’s all storytelling. And storytelling is an effort to get at the truth. Even a poem is a story; it always has a bit of a plot. Every form I work in is a version of storytelling, and I’m trying to find a story that interests me. It might’ve come out of my own life, Walter Benjamin’s, Robert Frost’s. I'm interested in people’s lives and stories.

AC: Among those incredible artists and thinkers, whose life did you find most difficult to capture in words, is there one that stands out? You can include Jesus.

JP: Jesus, yes, those were the hardest interviews. Every one of those biographies presented its own challenges. William Faulkner was a very complicated writer, and it broke my brain trying to wrap my mind around him and his fiction. Gore Vidal was challenging because he was a close friend of mine. He was a difficult, strongly alcoholic man which presented personal and emotional challenges. Robert Frost was the most satisfying biography for me because I love Frost’s work and have lived in Frost’s world in New England.

ET: Do you have any early memories of realizing you wanted to become a writer? Have you always wanted to be one?

JP: Early on I thought I wanted to be a stand-up comic. I think I’ve kept that going, that’s what teaching is for me. Teaching is strangely a version of stand-up comedy — the comedy keeps the material alive, keeps students engaged. I love audiences and performing. I wanted to be a poet, only a poet, at first. And then I realized I had to make a living, which was a bummer.

So, I did a Ph.D., but it didn’t satisfy my urge to tell bigger stories. So, I started writing novels, and at the end of the day I’ve written ten novels. It sounds more impressive than it is. It’s just a question of one word after another, one year after another. You have to be lucky, have good health and energy and have the wish to do it. It takes a great deal of patience. You’ve got to maintain your ambition, and at times that can be rather demoralizing. You make false starts. I have a lot of projects that are in the drawer, where they belong.

AC:I think a lot of young people encounter a figure — an author, if it’s writing —who opens their eyes to the world of literature. Was there a person or a few people like that in your adolescence who inspired you to go in that direction?

JP: I came from a very working class family in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Nobody in my family read books let alone wrote books. So there were no books in my family except “The Bible.” The high school I went to, West Scranton High School, had 3,000 students and the vast majority of my classmates went off to fight in the Vietnam War. A very small number went on to college. So, I didn’t have any models before me to think about becoming a serious writer or even reader.

The first writer I met was Alastair Reid, a Scottish poet who wrote for The New Yorker. He was amazingly influential in my life. The movie “Borges and Me” is partly about my relationship with him. He was my mentor who introduced me to a lot of other writers, taught me about the literary world and inspired me.

CL: Would you say that growing up in this relative literary vacuum has somehow deepened your sensitivity to narrative?

JP: My mother, though uneducated, was a great storyteller. In my family of origin, everybody sat around and told stories and made jokes, which was a very supportive environment.

My students from Middlebury come from middle class families where there’s a lot of pressure and competition; they’re in a race of some kind. I never had that impediment. I think I lucked out. The vacuum I came from was in some ways generative.

ET: While we’re in this sort of reflective mood, do you have a favorite memory at the college that you’re carrying with you to retirement?

JP: I remember certain writers that came to campus. Those were exciting moments for me. One year in particular, I invited Adrienne Rich, Seamus Heaney, and Mario Vargas Llosa. That was thrilling. With each of these speakers, we filled the Chapel, with standing room only. We had students talking to them afterward and the conversations spilled into weeks and months. To me that was a really great example of what the college can be: a place of conversations.

I remember my classes vividly. I’ve really loved teaching here over the years. I’ve had smart students and many of them have gone on to become writers and stay in close touch with me. It’s an ongoing relationship.

CL: Do you have any advice for young writers who want to build their lives around storytelling and meaning making?

JP: You only need one thing, which is discipline. I would urge people to develop a writing practice where they set aside a certain amount of time every day, keep a journal, write their ideas down and write everyday. It needn’t be a long period of time. One of the best pieces of advice I had from a writer was early on, I wrote to the brilliant and prolific Pennsylvania writer John Updike saying “I really like your novels and stories” and I met up with him for lunch at a McDonalds.

He said, “Just do two or three pages a day, and at the end of the year that’s over 600 pages, that’s two full books. If you just do two pages a day and keep consistent, you will have a shelf of books by the end of your life.”

ET: And you do have a shelf!

JP: I do have a shelf, over 30 books published. Maybe too many books.

ET: What are you reading now?

JP: I am reading a 600 page biography on Ian Flemming, author of James Bond. It’s a fun book to read. I read all kinds of books: popular biographies, more serious biographies, serious novels, crappy novels, poetry, criticism. I always go back to the classics: Frost, Wallace Stevens and T.S. Eliot.

AC: Is there a form of writing that you feel like your brain naturally feels more comfortable in? Poetry, criticism, prose?

JP: My most natural form is poetry, but I like memoir as well. “Borges and Me” came easily, and it felt good. My wife thinks I should’ve been writing memoirs from the beginning. I could never resist telling stories from my own life to students. It got to be an embarrassment.

ET: They’re really good stories, though.

AC: Maybe it’s a characteristic from your storytelling family.

JP: Yeah, I think that’s exactly what it is. I love telling stories, and in class I have always told lots of stories. But, I am 77 years old, at a certain point you have to stop. I have books I would like to finish and I’d like to do another solid 10 years of writing.

AC: Another movie or two?

JP: Another movie or two, that’s the theory of the thing. But I also hope that the students will stay in touch with me. That's the hardest part of giving up teaching. I love talking to students. I get a lot from those conversations.

ET: Do you have any more wisdom to impart?

JP: There’s no reason why anyone can’t be a writer. So many of my students have gone off and published novels, memoirs, written and directed movies. It’s amazing how many of them have done things. There’s no end of possibilities.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Christy Liang '28 (she/her) is an Arts & Culture Editor.

She is an English & Religion major who loves long conversations, live music in underground bars, and movies that are a little pensive. She's genuinely curious about what goes on in other people's minds.

Anthony Cinquina '25.5 (he/him) is an Arts and Culture Editor.

Anthony has previously worked as a contributing writer to the Campus. He is majoring in English with a minor in Film and Environmental Studies. Beyond The Campus, Anthony works as a writing tutor at the CTLR and plays guitar for a rotating cast of bands.

Ellie Trinkle '26 (she/her) is the Senior Arts and Culture Editor.

She previously served as a News Editor and Staff Writer. She is a Film & Creative writing double major from Brooklyn who loves all things art. You can typically find her obsessively making Spotify playlists, wearing heaps of jewelry, or running frantically around campus.