The college announced last month that it will implement a complete overhaul of its compensation structure, effective July 1. The decision is in part a response to an institution-wide wage study commissioned by the college that found Middlebury is currently paying 45% of its staff at rates below competitive market wages. The Mercer Study is a broad wage and salary survey across all departments commissioned by the college every few years and defines “competitive wages” as within 15% of the market median.

The college’s undercompensation of staff members has been a large issue for years. In 2019, some staff members began the process of unionizing in response to a myriad of workplace issues at the college — with low wages being one of their primary concerns. In response to the emerging union campaign and large student protests advocating for increased staff wages, the college increased pay for some entry-level staff positions in January 2020.

During the early stages of the pandemic, Middlebury froze staff pay even as their workloads increased, further upsetting some of the college’s lowest paid employees. Over the last year and a half, certain key staff departments remained drastically understaffed. In 2021, the college gave faculty and staff a 2% wage increase and one-time $1500 bonus. Still, housing costs in Addison County and Monterey increased and wages struggled to keep up. And in a September Staff Council survey, 46% of respondents said that they needed a second job to make ends meet.

Originally announced in March, the new compensation structure will tie Middlebury staff compensation to the wages at peer institutions. As the full implementation has not been finalized, human resources is releasing details of the plan slowly, with new information added every month. The college has set up an FAQ page to try to answer the litany of questions generated about the new compensation structure. While the new compensation approach is welcomed by many, some faculty and staff hold reservations about certain details of the project.

Mercer compared Middlebury to a comparison market of other colleges and universities such as Wesleyan, Lehigh and Smith, and found that only 46% of staff salaries were “competitive” in the defined market. Mercer developed this comparison market from schools that share similar operating expenses, student enrollment and geography with Middlebury. Compensation competitiveness was not distributed equally across positions: Over 60% of maintenance staff were making less than 15% of the market median while no one in human resources was making either less than or more than 15% of the market median.

In response to these findings, Vice President of Human Resources Catilin Goss is spearheading a new compensation model for all staff, focusing on immediately increasing wages for the least compensated staff members at the college.

“Just at a high level, the goal is really to pay everyone fair and competitive wages,” Goss said in an interview with The Campus. “It’s really important to us that we’re increasing pay for our lowest-paid employees so they’re fairly compensated, and we’re bringing their salaries in line with the market. It’s a top priority for Middlebury.”

The new compensation initiative will be funded by three different sources of revenue, according to David Provost, college treasurer and executive vice president for finance and administration. The three revenue sources are the endowment, budget reallocations and tuition.

In an interview with The Campus, Provost stated that the recent 4.5% tuition increase for next year was motivated by inflation and “pressures on [staff] compensation.” But the largest source of revenue for the increased compensation is the reallocation of money from other areas of the college’s current operating budget to staff wages. The college’s operating budget for FY 2022 was $283.4 million.

“We went to all of [Senior Leadership Group] SLG and we said, ‘Okay, we currently spend $300 million. Could we spend it differently? Could we throw more at compensation?’” Provost said.

According to Provost, the members of the Senior Leadership Group (SLG) were tasked with finding 4% of their operating budgets which could be reallocated to staff compensation. Provost explained that, “some found 1%, some found 4.5% [and] some found 0%.” Provost clarified that some departments, such as Health Services, actually discovered a need for a larger budget through this process, and that departments that have already been subjected to budget cuts in the recent past, such at the library, will not be cut further.

Professor Mike Olinick, current president of the Middlebury chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), thinks that such budget reallocations might hurt the college.

“We went through an exercise a few years ago to see what Middlebury should give up doing to try to contain its costs,” Olinick said in an interview with the Campus. “The end result was that they cut the size of the staff, but didn’t cut the amount of work that needed to be done.”

Yet Tim Parsons, college horticulturist and former president of Staff Council, differs from Olinick in his characterization of the previous audits, saying that he doesn’t think that a meaningful reconsideration of budgets has been done before. “There’s a lot of room to refocus our spending to be more student-centered,” he said.

The challenge of budget reallocation will be compounded by the rising costs of goods globally. According to one Dining staff member, who spoke to The Campus on condition of anonymity due to fear of retribution from management, the Dining Services budget is projected to increase 13–18% in the next year due to supply chain issues and inflation.

Compounding the plan’s uncertainty is the fact that the incoming Class of 2026 and their tuition hasn’t been finalized yet, so the college doesn’t know how much of that money could be available for increased compensation. Because Middlebury is need blind, they will not know the proportion of the incoming class that will pay full tuition and the proportion that will be given financial aid.

“Caitlin [Goss] is moving forward and simulating what it would look like if she had a pool of $5 million, $7 million, $10 million,” Provost said. “As we hone in on this and get closer to the middle of May, we will choose that number and communicate that with everyone.”

Though the new plan focuses on the lowest compensated at Middlebury, some are still apprehensive about just how much that will help.

“A lot of the time in situations like this, the top levels tend to make out a lot better than the bottom levels,” the anonymous dining staff member said in an email to The Campus. “The reality is, who needs that compensation more? The ones that make $70,000 or the ones making $35,000 and are living paycheck to paycheck.”

“Vermont is, in many ways, a very expensive place to live in comparison to some of the other cities where NESCAC colleges are,” Olinick said in an interview with The Campus.“I think there’s been a myth that some of the trustees have bought into, that we don’t need to pay workers in Vermont as much because it’s cheaper to live here. It’s certainly not true.”

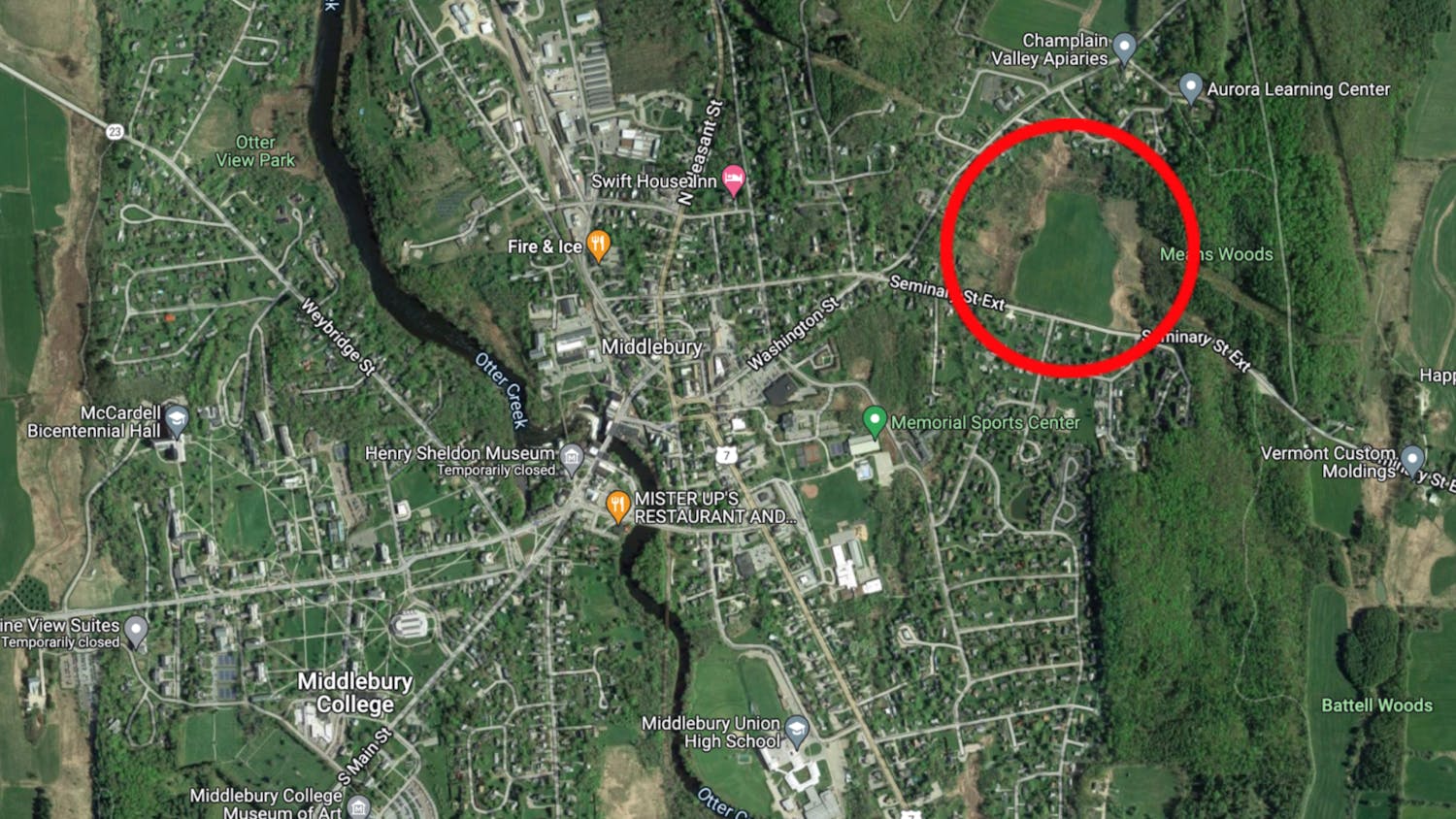

For the Vermont campus, the new model will not consider the local cost of living. However, compensation for positions in Monterey and Washington D.C. — Middlebury in D.C. is an administrative office which “provides a wealth of resources” for alumni, faculty and students — will be 15% higher than the compensation for their Vermont counterparts due to “geographical difference.”

One facilities staff member, who spoke to The Campus on the condition of anonymity due to fear of retribution from their manager, questioned if the new plan was ambitious enough.

“How come we’re just shooting for the bottom [of the market]?” the facilities staff member said in an interview with The Campus. “You’d think Middlebury would want to be a little bit above market and say, ‘Look, here’s what we’re doing for our people.’”

Parsons remembers when the college was the employer of choice in the area and hopes Middlebury can reclaim that title.

“I started in 2006, and all of my friends were amazed I got a job here because it was so hard to come and work at Middlebury college,” Parsons said.

The anonymous facilities staff member was also concerned about how well the market data the college used would reflect current inflationary realities in the economy.

Provost clarified that while he hoped the recent rise in inflation would only be an issue in the short term and long-term inflation should be included in the college’s new model. He also mentioned that given the realities of data latency, the college’s new market strategy will never be completely up-to-date.

On April 8, faculty overwhelmingly voted to approve a motion urging the administration to raise all employee wages 10% in response to rising inflation. An amendment to the motion which sought to prioritize raises for employees making less than $70,000 a year failed.

“We are acutely aware of the impact of inflation, especially on the lowest paid,” Provost said. “That impact to someone being paid $40,000 is significantly more than someone getting paid $140,000.”

At the individual level, the new compensation plan will completely change how employees are evaluated and thus, paid. While the market sets the compensation range for a given position, ultimately managers will decide position compensation.

The college will be getting rid of the Annual Performance Summary, or APS, the current structure of employee merit evaluations. Instead, under the new plan, managers will evaluate employees using a “skill matrix based on ownership and impact,” according to an HR presentation given to staff in March.

Goss said she hopes that this new, regimented process will actually improve employee and management relationships around compensation. “Sometimes these are hard conversations. But I think clarity is really, really helpful. And this [process] is built with transparency and clarity at the center of it,” she said.

But not everyone holds such optimism for the new program’s effect on the workplace. After speaking with The Campus, the staff member in facilities requested anonymity in part because “the new wage structure is going to be, in a sense, how your manager thinks you’re doing. You probably don’t want to make them mad.”

Jake Gaughan is an Editor at Large.

He previously served as an Opinion Editor and News Editor.