Over time, and at an accelerated rate since the beginning of the pandemic, housing prices have generally climbed across the country, and Addison County, Vermont, and Monterey, California — the location of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies (MIIS), and one of the most expensive places to live in the U.S. — are no exceptions. These increases in housing prices intimately affect staff members at both Middlebury campuses, impacting their daily lives, families and quality of life.

Here in Addison County, many may have heard the refrain that retreat from cities in the Northeast during the early stages of the pandemic led to dramatic increases in housing demands and prices. Matthew Curran, Middlebury College’s director of business services, elaborated on this phenomenon. People moving to Addison County in March 2020 were often coming from more expensive cities and could afford to pay well over the asking price or to pay in cash. Now, almost two years later, many of these people have chosen to remain in Addison County.

“I think a lot of people expected it to kind of flip, for people to move back. People are staying here because of the quality of life, [and] being able to work remotely,” Curran said.

While this population growth is good for the state in some ways, it has also catalyzed the preexisting trend of increasing housing market rates in Vermont. Rising prices have made the search for housing tougher for many locals, including college staff. According to Tim Parsons, a landscape horticulturist at the college, some staff have resorted to living in upstate New York and commuting to work to secure affordable housing.

For Katie Tatro, a staff member working as a dishwasher in Atwater and living in Cornwall, high housing prices have created a barrier to buying a home where she would live with her 11-year-old son. Tatro has worked at Middlebury since she graduated high school, around 25 years ago. In her time working here, Tatro has worked in all dining halls and departments and done laundry. She switched to working as a dishwasher because it often enables her to go home early and spend time with her son when he is home from school. However, Tatro mentioned working double shifts and emphasized she stays flexible in her hours and rarely calls in sick.

Tatro, a single mother, currently rents a three bedroom, one bathroom home with her mother, where the two live with Tatro’s son. Her landlords also work at the college, and her rent has not increased over time. Still, Tatro aims to own a home, and she emphasized that despite paying her bills on time and maintaining good credit, she has been unable to purchase one.

Tatro has also looked at other rentals, but the prices are a deterrent. “It’s really really expensive everywhere,” she said. “Rent is going up.”

Reflecting on her career and position at Middlebury, Tatro was resolute. “[I’ve] been here forever,” she said, adding she will likely work for the college in the future despite these issues. When asked what she wished the college would do differently in terms of housing, Tatro mentioned the college’s promise to fix wages in the near future. When prompted, Tatro mentioned it would be a positive if the college provided housing for staff, but said she knew this depends on the position an employee holds.

As Curran explained, Middlebury’s current housing for employees only provides for faculty, a norm created before his time. The college owns 72 units in town, and Middlebury acts as the landlord for these units. This year, for the first time in a long time, 100% of these units are full. The units are rented to faculty at near market rate prices, in an attempt to ensure the school is not harming town markets. Housing stays are limited to six years, or one year after a professor gets tenure. These measures ensure Middlebury is not monopolizing the housing market. Housing is often used as a draw to attract faculty to the college.

“Housing is used as a recruitment tool,” Curran explained, adding, “Not many faculty are from the area, and most staff is local.” This means that most faculty have some housing conditions written into their agreements to support their move to Middlebury. Generally, this is not applicable to staff, who often already live in the local area.

Additionally, the college has a second mortgage program, where the college helps subsidize mortgages for faculty. If a faculty member qualifies for this program, a determination made in their appointment letter, the college can sign on to their mortgage as a co-lender, and sign as a second mortgage for up to half of the house. Most staff do not “qualify,” meaning they don’t have this support negotiated into their contract.

Through staff benefits, however, the college has an employee assistance program. Curran himself mentioned talking with staff and putting them in touch with brokers and landlords to help staff find affordable homes. The lack of infrastructure for staff housing, however, presents an issue for staff that faculty do not face.

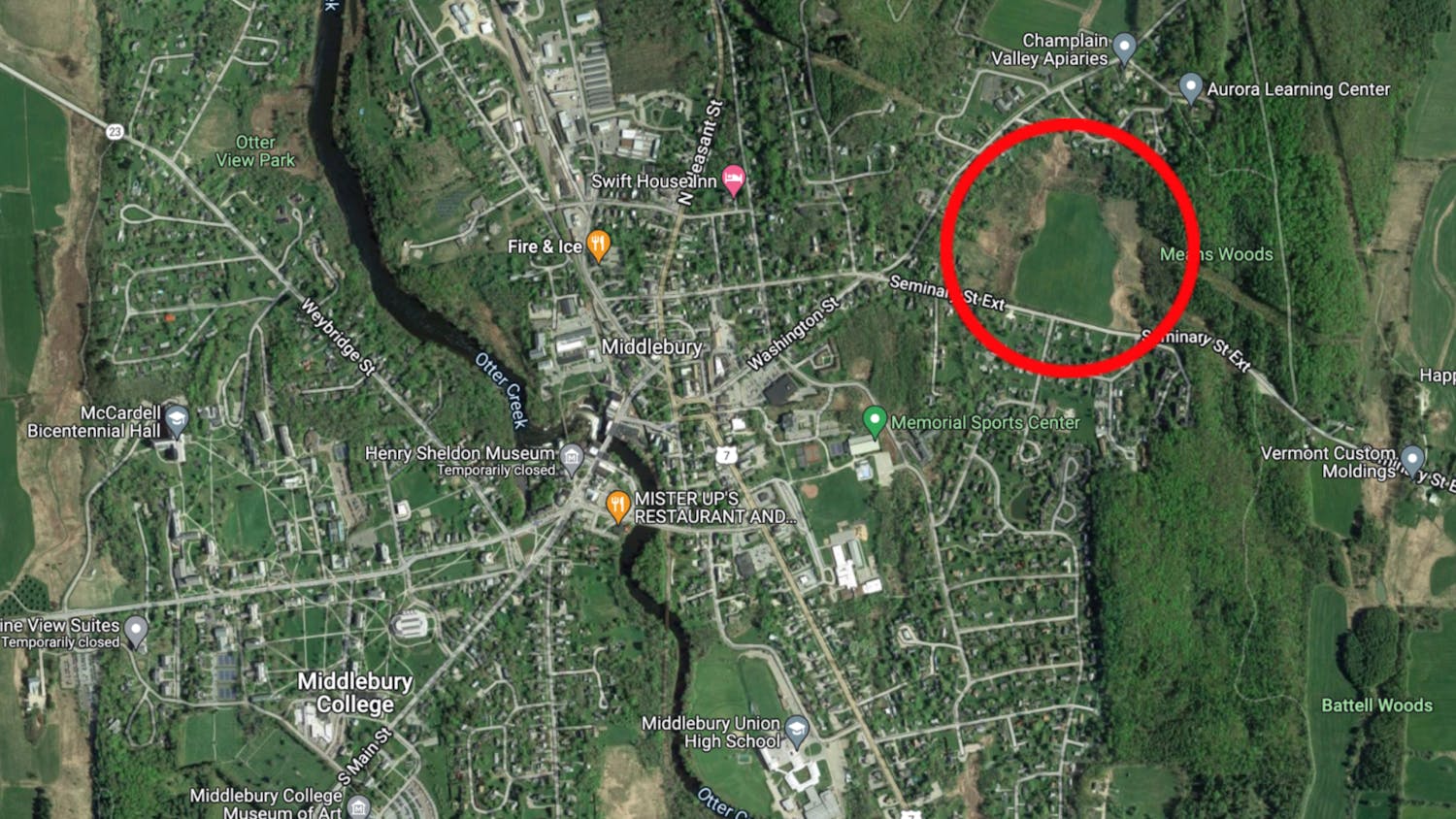

Curran recognized that in general, Addison County needs more housing. He discussed the college’s interest in working with local government as well as developers to build more homes in the area on land the college already owns. This housing would ideally be available to help ease the strain on housing. At the moment, however, it seems evident that amidst a difficult housing market, staff face larger burdens for finding housing than faculty.

As for MIIS, the city of Monterey, home to the institute, is one of the most expensive housing markets in the country, and several aspects of Monterey’s housing landscape make it different from Middlebury.

First, Monterey only owns one four-unit apartment building. Bought by an anonymous donor in 2006, two of the units are dedicated as guest housing, provided for visitors to Monterey such as administrators or professors from Vermont, for example. The two downstairs apartments, however, are set aside for staff. As in Addison County, these units are meant to entice employees to move to Monterey. In Monterey, however, both units are rented to staff, not faculty, at a rate considerably below market price; both are meant to be used as long term rentals. Monterey does not have any other employee housing.

MIIS housing is limited in other ways: only in fall 2021 did Monterey start providing dormitory housing to its students, and the majority still live in off-campus housing.

Another key difference between MIIS and Monterey is the fact that MIIS relies on contracted custodial staff. As Barbara Burke, executive assistant to the vice president of Monterey, explained, MIIS has a contract with an outside agency that provides custodial staff for the school. Details on the wages of these staff are less known, and MIIS generally has knowledge of what the school pays the agency as a whole, rather than individual staff wages.

Staff at MIIS also generally have higher wages than staff at Middlebury, due to California minimum wage and the high cost of living. As Burke explained, all staff make at least 18 dollars an hour, and most make more than that. Staff employed by MIIS make more on average than college staff, because they include those working in the financial aid office, Human Resources, media services, the library and more. This different niche of MIIS staff impacts the provided wages and influences how staff navigate housing.

Still, housing can be difficult. Some staff live in other parts of Monterey, which, while technically still a part of the area (Salinis, for example, is a 15-minute drive away), are less touristy and therefore less expensive than the heart of Monterey. As Burke remarked, Monterey is beautiful and has a lot to offer. But it’s also expensive.

Joelle Mellon, a research and instruction librarian at MIIS, teaches library skills to students and helps people at MIIS find information for papers or projects. Although Mellon is happy with her current living situation, it took her almost two years to find a satisfactory living arrangement.

Mellon’s housing journey indicates how difficult finding housing in Monterey is: after living with two sets of roommates in two different houses, Mellon lived in an RV for almost a year during the pandemic.

“Somewhat absurdly, I then moved into an RV for almost a year, since it was one of the few places I could afford to live alone,” she said in an email to The Campus.

Living alone became a necessity once the pandemic led to her working from home. Finally, she found an affordable studio apartment in Seaside, a nearby neighborhood. The apartment is tiny, but not far from the school. It is also near a beach and restaurants. Plus, she said, the weather in Monterey is fantastic.

Despite her difficulties finding housing, Mellon had positive things to say about the MIIS administration’s role in housing.

“I want to emphasize that it isn’t the fault of anybody at Midd or MIIS that getting a place to live around here is so hard,” she said. “The Monterey area is just an incredibly challenging housing market. After I was hired here, I cannot tell you how many times an administrator spontaneously checked in with me to ask about how my housing search was going. They genuinely care.”

She added, however, that an official staff and faculty network to help acclimate new hires to the area would be helpful.

Mellon stressed that it is possible to find decent, affordable, housing in Monterey.

“You just need to put the time, energy and effort in that’s necessary to get it (although a bit of luck doesn’t hurt)” she said. “I wanted the chance to tell folks who are currently looking for an apartment what worked for me,” she added.

In her housing search, Mellon first used Craigslist and then switched to Zumper, a database specifically for apartments. She found their database more reliable. Mellon stressed the immediacy needed in the Monterey area.

“I had to check Zumper at least once per day, every single day… The housing market is so ridiculously competitive in the Monterey area that nice, affordable apartments will get taken within hours of being posted… If anything came up that looked like it had potential, I acted on it immediately, calling or texting the landlord(s) literally within minutes,” she said.

This process required making big decisions, like signing a lease, at a moment’s notice.

Despite the stressors involved in finding a house in Monterey, Mellon said staff are able to laugh at the process.

“MIIS employees usually have a pretty good senses of humor, so there was a lot of joking around about us all living in garages. But I think that quite a few of us were worried about how hard it was to find a place we liked that was even remotely affordable,” she said.

Both in Monterey and in Addison County, staff struggle with housing. Although there are numerous factors beyond the college’s control, staff who spoke with The Campus felt that a heightened understanding of the issues can create better understanding, as well as lead to actionable steps the college can take such as providing support forums, higher wages, and staff housing.

Julia Pepper '24 (she/her) is the Senior Local Editor.

She previously served as a Local Editor. She is a Psychology major and French minor. This past spring she studied in Paris. She spent the summer interning at home in New York City, putting her journalistic cold calling skills to use at her internship doing outreach with senior citizens. In her free time she enjoys reading and petting cats.