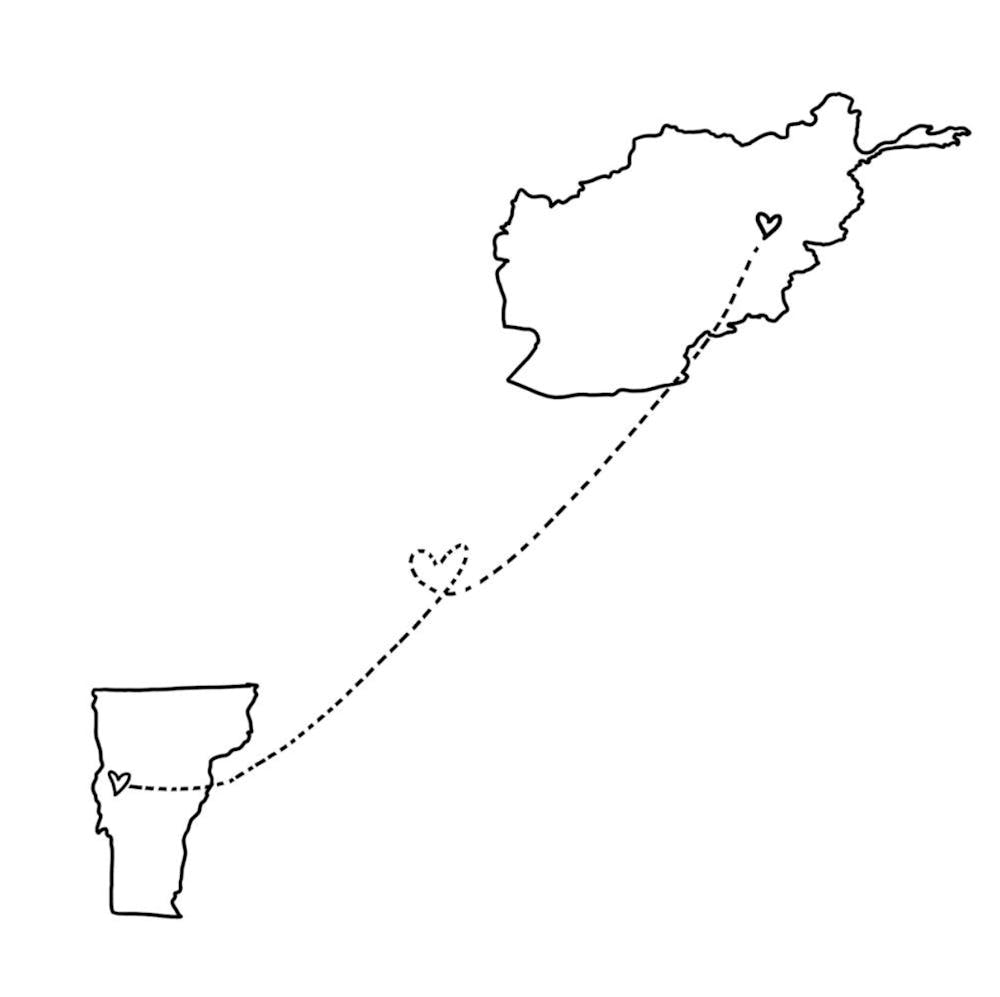

In January 2022, eight young women from Afghanistan arrived to begin their Middlebury College educations over the frigid winter break. The quiet mountain landscape and gray limestone buildings displaced the skyscrapers and big screens they had imagined when they thought of the U.S. Other students had not yet returned to campus, and the dining halls and dorms felt eerily empty.

“I thought I would be so ready, but I wasn't,” Lima Abed ’25.5, who had already completed a four-year degree at the Asian University for Women in Bangladesh, said. She will earn another from Middlebury in International and Global Studies at the end of this month. “I wasn't ready at all.”

More than four years after the Taliban took over Afghanistan, forcing the women to leave behind the lives, passions and educations they were pursuing in and around their home country, their Feb graduation is almost here. They have overcome immense challenges and achieved remarkable accomplishments, but are now faced with still more uncertainty in figuring out how to continue to follow their dreams in the U.S. in a political climate that has become increasingly hostile to Afghans.

Abed had just begun renting an apartment in Kabul in August 2021. She was starting a fellowship working for the Ministry of Interior in the Afghan government, determined to help women gain greater rights and power. Then, the government collapsed, and the Taliban entered. In a matter of hours, her life had completely changed.

“Everyone was running, everyone was finding a way to get out of the place,” Abed said. “I was like, this is not real. This is a bad dream.”

She and the other future Middlebury students fled first for Qatar and then to Rwanda. The founder of their former school helped them apply to Middlebury, and five months later, they arrived in the Green Mountains.

Their first semester was isolating and demanding as they continued to grieve the loss of their country. They were not familiar with the American games intended to bond groups at orientation, and some of their classmates who had been friendly the first week stopped greeting them, Abed said, even in passing. Having set out with the exciting aspiration of getting to know a new culture, they hadn’t intended to spend most of their time together or with other international students. But often, it felt like the only safe option.

“I remember very dark days outside,” Sajia Yaqouby ’25.5, who will graduate with a degree in History of Art & Architecture, said. “But when I think about it, it was [dark] mentally as well.”

“So it was so difficult, so difficult,” Abed said. “At the same time, that made us very strong.”

The faculty in the classes Abed, Yaqouby and the others in their cohort took helped them immeasurably, they said, becoming close friends and mentors that pushed them to survival and later to success. As Abed worked hard to understand the American poetry in her first year seminar, Literature and Moral Choice, Professor of Writing and Rhetoric Hector Vila recommended she add in something more light-hearted to balance her schedule: Acting I. She was shy in class, she said, but enjoyed participating in the dancing and speaking activities. With her professor’s encouragement, it became her favorite part of the week.

Yaqouby and Taniya Noori ’25.5 took Sexuality and Power on Stage for their first year seminar, reading and writing about sex, gender and theater — topics that would never have surfaced in the classrooms they had been in back home.

“What if I say something and it's offensive?” Yaqouby recalled thinking. “I am a very quiet student overall, but then in that class I was very, very careful.”

As the women continued and completed more semesters, their confidence in the classroom and in other parts of campus life grew. They conducted research and learned more languages. They took on internships and jobs, with many working in Circulation Services and Information Technology (IT) in the library.

Yaqouby discovered her passion for her major while taking the course Mughal Art with Professor of History of Art Cynthia Packert. Afghanistan is part of the larger Persian artistic tradition, and she could read the Persian in the manuscripts the class examined. She was struck by how little of the material she had learned in her previous education, even in her two years at the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan.

“I think that's where my interest really got deeper because I was like, we need to talk about this stuff, right?” Yaqouby said.

Setting out to fill in the gaps, she worked towards her senior thesis with Packert on 19th-century Kashmiri manuscripts. She earned the Kellogg Fellowship, which enabled her to study the works up close at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C.

Abed completed an internship at the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI) in Burlington in 2023, which inspired not only her goal to keep working for organizations that help newcomers to the U.S., but also to focus her IGS degree on migration. Her thesis is on Afghan women’s experiences with land migration, for which she traveled to New Mexico to meet and interview an Afghan woman who crossed through 13 countries.

Noori started an online tutoring program for girls in Afghanistan while at Middlebury. Through the Mellon Migration Fellowship, Yaquoby conducted research on art and refugees, and is working with a group of Afghan artist refugees in Vermont to create a mural project called “Colors of Home” to display in Proctor Dining Hall.

The interests of the young women range from health care to religious ethnography to politics and more. Abed, Yaqouby and others from their cohort have participated in the Middlebury Language Schools, taking immersive Arabic and Spanish. They said that language programs and classes helped them make more friends from all backgrounds and feel increasingly comfortable in the community.

“I had so much fun. I was me. I was so social with everyone,” Abed said about the Arabic School. “Everyone was at the same level. Nobody was judging anyone.”

Yaqouby and Abed described feeling stuck between the urge to help people learn about Afghanistan and advocate for better lives for the people in the country they call home, and wanting to feel and be treated like regular students. People have asked them about the Taliban immediately upon finding out where they’re from — questions that bring up difficult memories.

“It's very complicated because on one hand, you want to talk about what's happening in your country — with everything going on, your experience, obviously it's important, it's valuable, people should know about it,” Yaqouby said. “But at the same time, you're like, how far do I want to take this? I don't want people to know me just by what happened four years ago in my life and not really know who I am as a person or as a student.”

Yaqouby plans to get her PhD in art history from a U.S. university, but wants to take time off and work first. After years and years of school in several countries, she is ready for a break.

F-1 International students are able to apply for OPTs, temporary work authorizations that last up to 12 months. The process to ensure they can stay in the U.S. is complicated, and tensions and uncertainty are high. The Trump administration in November halted all asylum decisions for Afghan nationals after a shooting by an Afghan man of two National Guard members in Washington, D.C.

“At this point it's getting very, very scary. Every single move you do, you get really worried,” Yaqouby said.

Some of her friends have suggested that she could go to another country. But to start over in a completely new place again would feel like an insurmountable task.

“That feeling of home that you find, it takes such a long time to do,” Yaqouby said.

Abed recently received her green card, which permits her to obtain her U.S. passport in five years. But she was not able to study abroad in Jordan in the fall as she had hoped, for fear that a national travel ban on Afghans would prevent her from safely returning.

“I didn't want to take the risk,” Abed said.

She worries discrimination against Afghans might prevent her from finding a job at an organization that assists refugees and immigrants, as she is determined to do. That won’t stop her from trying. To her relief, she was able to help her parents relocate from Afghanistan to Dallas, Texas, in November 2024, where she will stay and continue applying for jobs after graduation.

“I’m really tired of moving,” Abed said. “That's why I'm planning to stay here and really help people who are coming from different countries because I know how it feels to be in a different country when you don't know the language, the culture or anything here. That's my hope.”

Editor's Note 1/23/26: The name of the school the young women formerly attended and some details about Yaqouby's immigration status have been removed from the original version of this article for security purposes.

Madeleine Kaptein '25.5 (she/her) is the Editor in Chief.

Madeleine previously served as a managing editor, local editor, staff writer and copy editor. She is a Comparative Literature major with a focus on German and English literatures and was a culture journalism intern at Seven Days for the summer of 2025.