“Broken Embraces,” by Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, is a love story noir chronicling the life of a filmmaker and his close relationships to his work, his agent and her son, and an actress in his film. The film opens on Harry Caine, a blind writer that we later learn is the pseudonym for Mateo Blanco.

As a director in his successful years, Blanco would write under the name Harry Caine and direct as Mateo Blanco. When he lost his sight, he abandoned the director name with his ability to direct and became his pseudonym, writer Harry Caine. While brooding, Caine is not a tragic figure. Despite having no sense of sight, he has developed the use of his other senses quite well, as evidenced by his seduction of a young, attractive model in an early scene.

However, a meeting with young filmmaker Ray X sparks a series of events that bring back memories from his past and the rest of the film is told in flashback form with Harry narrating a tragic story of love, jealously, and guilt.

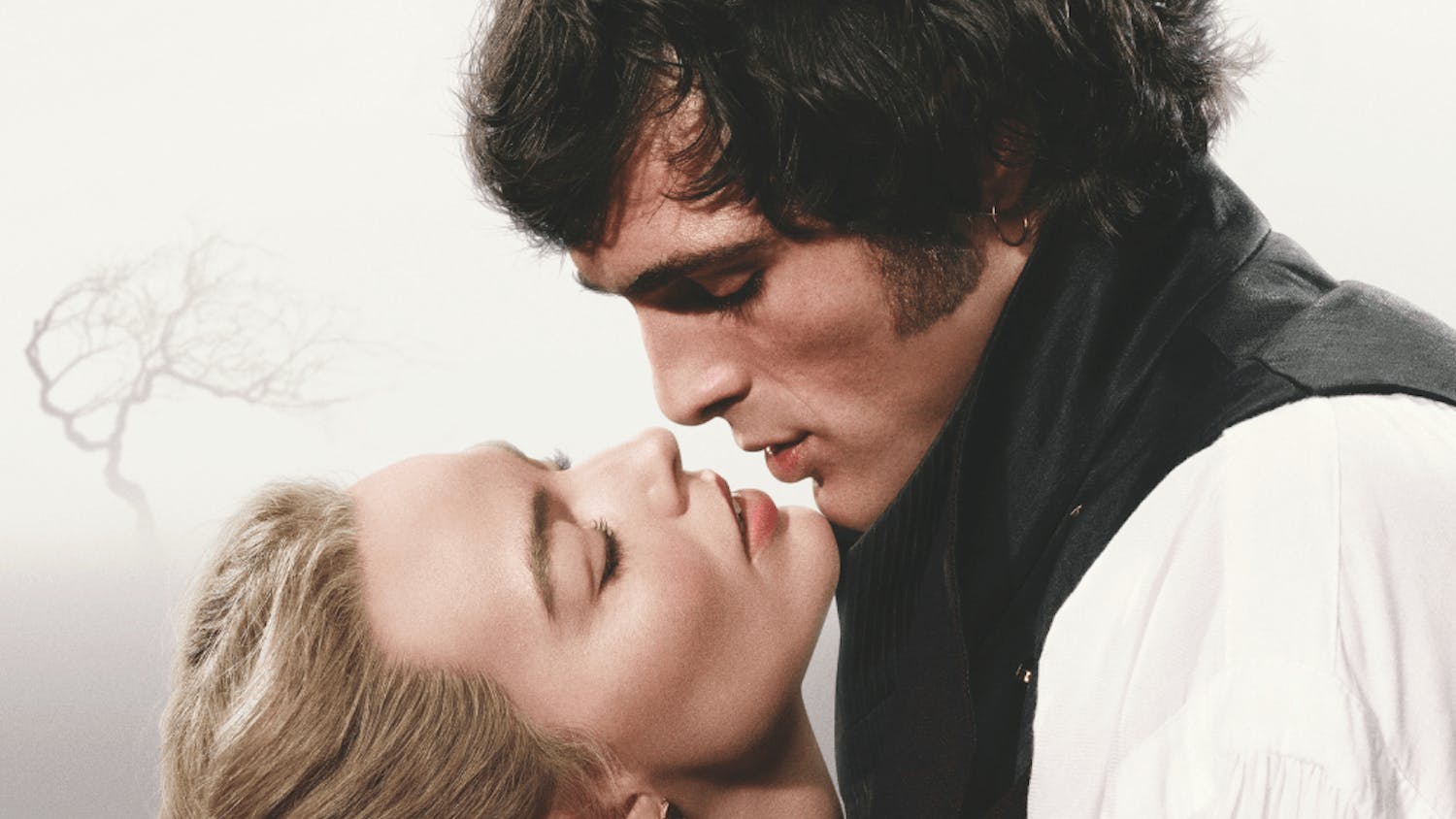

The star of the flashbacks is Magdalena Rivas, portrayed strikingly by Penelope Cruz. Lena is an office worker and part-time prostitute who gets into a relationship with an older millionaire, Ernesto Martel, in order to pay for her father’s medical treatments. Eventually she becomes Martel’s mistress and decides to audition for

“Girls and Suitcases,” Harry Caine’s (Mateo Blanco) new film. Lena gets the lead role, and through her close work with Caine on set, becomes romantically involved with him. Suspicious, Martel hires his obsessive son to film the two on set and then hires a lip reader to interpret their conversations from afar.

Once he is sure that Lena is sleeping with Blanco, Martel becomes abusive and Lena escapes with Harry to a small beach island where Lena seeks work. There, Harry sees a negative review of his film in a newspaper and on his way back to Madrid gets into a car accident, killing Lena and taking his sight and identity as Mateo Blanco.

Meanwhile, in the present time, Judit reveals more details about the past and Harry decides to re-cut the film that he learns had been sabotaged by Martel upon its release. The film ends with a scene from “Girls and Suitcases,” a scene reminiscent of Almodóvar’s early film “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.”

The story is a classic tale of betrayal told fairly formulaically as a typical film noir. Overly theatrical writing and a tense score heighten many moments of dramatic tension. From a writing standpoint, the film is not one of Almodovar’s best efforts due to flat character work and too much expositional writing featuring long monologues about action we never see on screen. Directorially, Almodovar does a good job getting a strong performance from Penelope Cruz who plays a darker and more humorless character than she usually does.

Seemingly more comfortable speaking her native Spanish, Cruz commands the attention of the viewer every moment she is on screen. Shot skillfully by cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, the film is visually stunning, with intense colors that stand out against the streets of Madrid. Scenes in the bedroom are particularly engaging, filmed so that the viewer wants and expects more intimate shots but, brilliantly, is left disappointed.

Cruz’s natural beauty on screen is augmented by Almodovar’s decision to have close-ups linger on her eyes and face. Unfortunately, after Cruz’s departure at the end of the second act, the film falls apart and rushes to an incomplete and untidy ending with little character resolution and a disappointing payoff. Longtime fans of Almodóvar will surely appreciate the metatheatricality of “Girls and Suitcases’” similarity to “Women on the Verge,” but by the end of the film, even that feels gimmicky and underdeveloped.

Overall, the film relies too heavily on Cruz’s appearance and performance so that after her exit, all of its flaws are left out in the open. The final sequence, a scene from “Girls and Suitcases,” only serves to remind the viewer of Almodóvar’s previous successes, ending the film on a bitterly nostalgic high note.

The Reel Critic - 02/18/10

Comments