As a super senior graduating this coming February, my college experience has spanned two distinct eras: before artificial intelligence (AI) and after AI. My introduction to AI came over Christmas break in 2022, when my tech-obsessed father showed me ChatGPT. My family crowded around my laptop, collectively testing its responses with wide-eyed curiosity. Back then, I felt ahead of the curve, part of a small group witnessing the dawn of something that might change the world. Three years later, as I prepare to graduate, I feel the opposite.

Despite the novelty, I wasn't particularly drawn to using ChatGPT. As a political science major who seeks out writing-intensive opportunities like The Campus, I believed nothing could replace the sensate, lived experience behind human creativity. ChatGPT hallucinated facts, struggled with nuance and at the time, its knowledge cutoff left a lot of information outdated.

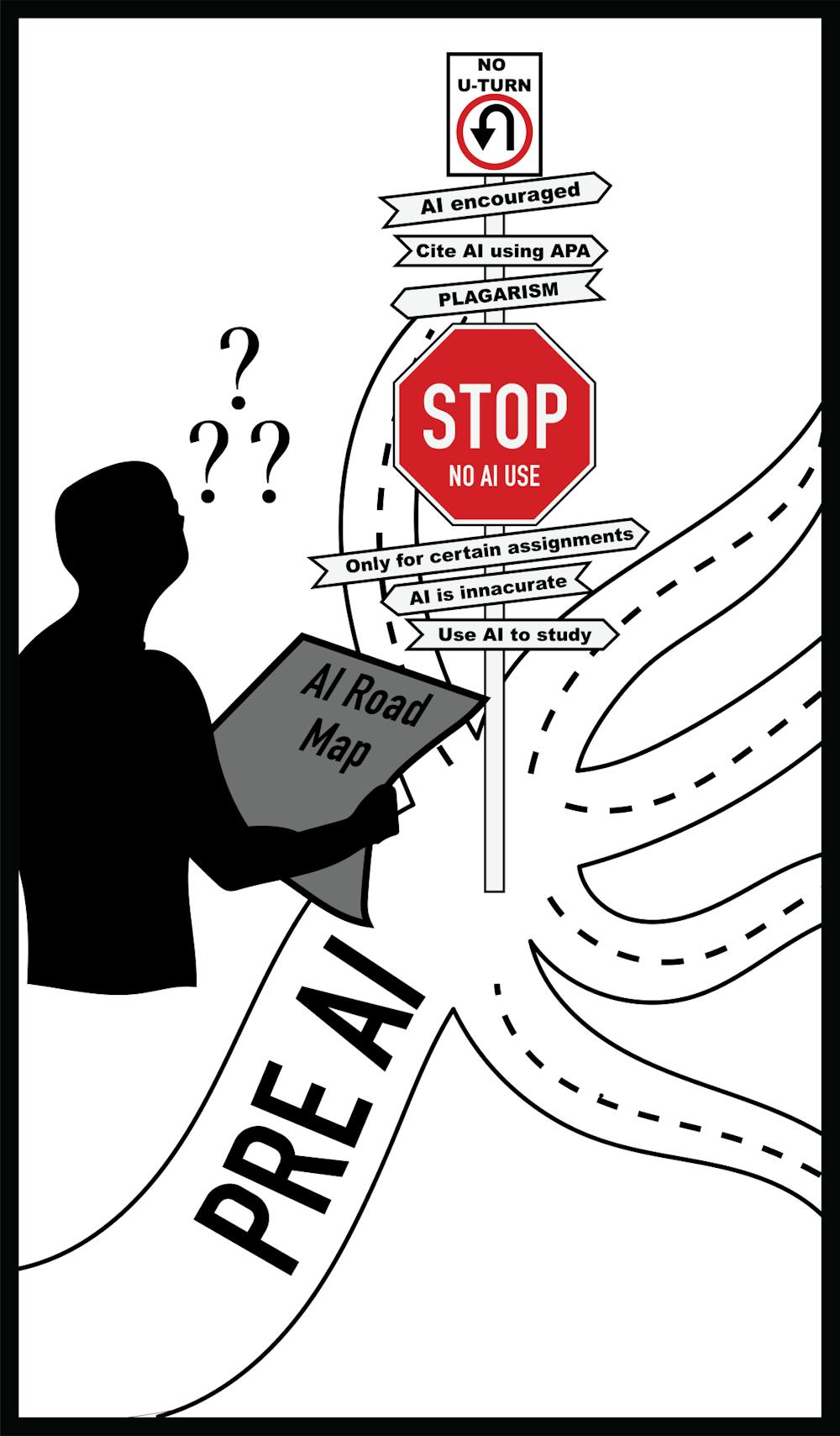

What began as cautious curiosity into the technology evolved into what Middlebury Distinguished Endowed Professor Allison Stanger aptly called a “theater of prohibition” at this fall’s Clifford Symposium. While I stuck with the “old-fashioned” way of doing assignments, some of my peers at Middlebury — and even more at other schools — were experimenting, learning how to collaborate with AI and slowly building fluency. I didn’t stumble across platforms with specialized functions until 2025. As graduation looms, I feel like someone blinking, only to realize the world has changed in that instant.

There's an unspoken expectation that young people should intuitively understand these technologies the same way we're expected to explain TikTok to our parents or teach older professors about the latest digital tools. Yet despite being part of the generation that supposedly ‘gets’ technology, I don't feel equipped to navigate AI’s complexities.

In my almost four years at Middlebury, only two of my courses have integrated AI into the coursework. One introduced the various tools directly, the other had us compare our writing to that of AI’s, leaving me feeling like my voice and authorship had been stripped away. It’s a stark contrast to my brother’s experience at the University of Pennsylvania, where AI is embraced openly. He tells me that it’s not about memorizing information anymore, but knowing where to look and what questions to ask. I asked him a financial question recently, and he told me: “Just ask Chat, it knows more than me.”

His default is the machine. Mine is still people, but I sometimes wonder if I’m the strange one because of that.

The reality is that AI is already reshaping not just how we work, but how we learn. We are now the first generation to be taught by humans and machines, replete with the anxieties it brings. Why ask a professor during office hours when ChatGPT is available 24/7? Why go to peer tutoring if an algorithm can walk you through the same material faster, without judgment, and with infinite patience? These tools make finding help accessible, but at the cost of human-to-human interaction, mentorship, and the messy but essential process of learning together.

Middlebury’s campus has been cautious. We tell ourselves that by keeping AI at bay, we are protecting our pure liberal arts ideals. But the truth is less romantic. Professors craft strict policies that they don’t fully believe in. Students conceal the extent of their use. Faculty quietly experiment with AI in their own research while discouraging us from doing the same. Everyone pretends this dance of deception isn’t happening, even as it erodes our Honor Code.

This silence comes at a cost. Prohibition doesn’t work — it only drives AI use underground. Instead, we need open, honest dialogue between faculty and students about what ethical AI use looks like in a liberal arts setting. What kind of work do we want to produce? What kind of thinkers do we want students to become? And how do we prepare for a professional world where AI use is not only accepted but expected?

There are clear boundaries, like asking AI to do your homework or write essays. The harder questions are in the gray areas. Is Grammarly AI? What about Speechify reading 300 pages of theory out loud, or NotebookLM turning PDFs into podcasts? Is asking ChatGPT to explain Russian grammar cases so different from having a personal tutor? Where is the line between support and substitution, augmentation versus automation? These gray areas matter for determining our own responsible use.

Students need help navigating these boundaries. Right now, we’re navigating alone. Speaking to a professor can feel risky, like a confessional moment where you’ll be caught. But I don’t think Middlebury students want to use AI as a shortcut. We chose this school to learn, to think, to create. The real question is how to integrate AI without losing those qualities.

Not addressing AI also leaves students unprepared for the post-grad reality where its use is expected, if not encouraged, in workplaces. It's about preparation for a world outside of academia that embraces AI for productivity, as companies are increasingly asking their workers to do more. As Parker Harris ’89 said at the Clifford Symposium, “The paralegal that knows how to leverage AI will do a higher value service for a legal firm than probably what they’re doing today, or what AI could do alone — same with a financial analyst.”

The conversation should go beyond academic integrity. When some students can afford premium AI tools while others cannot, it becomes about equity. It's also about literacy, the way financial literacy once became a core competency. And it’s about culture. Larger society still prizes output, productivity and résumé lines over uncertainty, contemplation and the painstaking process of thinking deeply. AI accelerates that culture. But it could also challenge it if we learn to use it with intention.

Personally, AI has now become both a temptation and tool. It can help me code for research, brush up on math problems I’ve long forgotten, brainstorm, generate visuals and organize club agendas. But it also tempts me to sacrifice depth for efficiency and trade a tedious process for a polished output that isn’t mine. My messy Google doc full of arranged and rearranged paragraphs, scattered sentences and suggestions to myself may be slower, but it makes me think harder and grants the reward of arriving at a final product that is all me.

Middlebury cannot ignore these tensions. Students want to learn, to think, to create. We don’t need AI to replace that. We need guidance, conversation and space to figure out how to integrate new tools without losing our humanity. Clearer boundaries and more faculty-student dialogue without “gotcha” moments could be a start.

It’s not about learning technical use, but rather ethical use. Middlebury should prepare us to engage with AI thoughtfully and coexist with it in ways that make us higher-functioning humans, not less. Our honor code depends on it. Our preparation for the future demands it. And our commitment to learning — the very reason we’re here — requires it. Let’s start having those conversations.

Ting Cui '25.5 (she/her) is the Business Director.

Ting previously worked as Senior Sports Editor and Staff Writer and continues to contribute as a Sports Editor. A political science major with a history minor, she interned at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. as a policy analyst and op-ed writer. She also competed as a figure skater for Team USA and enjoys hot pilates, thrifting, and consuming copious amounts of coffee.