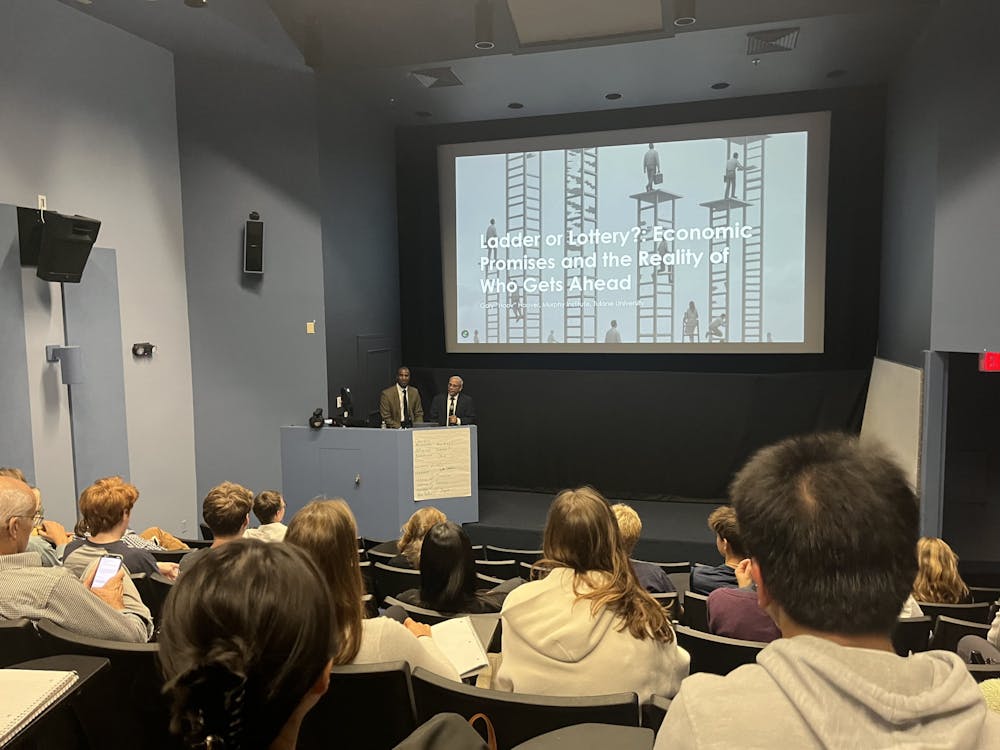

Approximately 50 students filled Twilight Auditorium last Thursday afternoon to hear economist Gary Hoover argue that America's promise of economic mobility may be more of a lottery than a ladder. The talk, part of the D.K. Smith Economic Lecture Series, featured Hoover promoting his book “Ladder or Lottery: Economic Promises and the Reality of Who Gets Ahead.” With his baritone voice carrying a hint of a southern accent, the Executive Director of the Murphy Institute at Tulane University held the audience's attention for an hour. College President Ian Baucom was among those in attendance.

“Is the lower rung on the economic ladder simply a choice?” Hoover asked, presenting the central question that inspired his research. “We're told that poverty is just a choice, that people are where they are because they choose to be there.”

Hoover defined these “ladders” as social contracts: society’s promises that specific actions will lead to upward economic mobility. Education, healthcare, entrepreneurship, military service and family formation, he argued, all carry hidden flaws that prevent many Americans from advancing up the economic ladder despite following the supposed rules. He also divided Americans into two groups: the “deserving” poor, whom society blames for not following the prescribed path, and the “undeserving” poor, who did everything right but still didn't climb.

He illustrated income inequality's growth with stark statistics. In 1970, the lowest 20% of Americans held 4.1% of income while the highest 20% held 42.4%. By 2022, those figures shifted to 3.5% and 50.7% respectively, meaning that over half of all U.S. income now concentrates in the top fifth of the population.

With quick wit and a knack for analogy, Hoover then illustrated the shortcomings of conventional “ladder” metaphors.

Sometimes, he explained, the rungs on an economic ladder are broken or missing entirely. Education may be compulsory and free, but quality varies so dramatically by zip code that straight-A students from some schools aren't equivalent to their peers from better-resourced districts.

Drawing on his three years of military service, Hoover shared how veterans' benefits came with hidden obstacles, such as mandatory $100 monthly paycheck deductions that hit hard when his total pay was only $330, or bureaucratic mismatches between the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) payment schedules and universities' tuition deadlines.

He linked past movements from Occupy Wall Street to the Arab Spring to the breakdown of social contracts, arguing that protests erupt when people do what society asks but remain stuck, feeling undeserving of their economic position. Hoover predicted two coming battles: artificial intelligence and affordable housing.

Hoover's central argument relied on an engineering principle: a properly designed system must produce the same outputs from the same inputs, repeatedly and predictably. With 64 million Americans in poverty, he argued that it is statistically impossible that none of them put in the same effort as successful individuals.

“If you design a system, that system must always, if you put the same inputs into it, it must repeatedly and predictably give you the same output,” Hoover explained. “If it doesn't, you have a design flaw.”

Even if the system works perfectly and the problem is “user error” — people not knowing how to use the economic system — then 15% user error in any other product would trigger an immediate recall. He used the example of children sticking forks into electrical outlets; child-protective devices exist because we recognize that design must account for human behavior, not simply blame users for misuse.

“If 15% of people driving onto a bridge keep running into the support pillars… soon enough the bridge is going to fall," Hoover said. "And then none of us are going to have it.”

When pressed on solutions during the Q&A session, Hoover offered two options: Tell people the truth that economic mobility is largely a lottery, or fix the system by going “all in” on making the social contract work as promised. He cited Medicaid as a program that lifted many elderly Americans out of poverty, but said most reforms have been half-hearted.

Questions from students and faculty pushed Hoover on policy prescriptions, from expanding Medicaid to addressing zoning laws that limit housing supply. While he responded vaguely and offered few definitive fixes, Hoover returned to his larger point that economic systems must be redesigned when too many users stumble, and that acknowledging the system is broken is the first step to fixing it.

Professor of Economics Caitlin Myers asked what small liberal arts colleges should do as stewards of the social contract. Hoover urged academics to “leave the ivory tower” and better articulate their value beyond job preparation, emphasizing the importance of education in reducing crime, increasing civic engagement and strengthening democracy.

“We have to show that there's a value in learning, there’s a value in science,” Hoover said in a post-talk interview with The Campus. “Because here's the thing that I find interesting: The groups don't talk to each other. The ultra wealthy are talking down to the ultra poor, and the ultra poor are just trying to survive day to day. They’re really sort of disconnected.”

Student reactions were mixed. Students appreciated Hoover's clear articulation of the problem, but wanted to hear more concrete solutions.

“It felt a little bit sad, almost, and informative, but also hard to take to the next step of action for myself,” Truett Ramsey ’25.5 said, noting the challenge of feeling powerless as a young person facing housing and AI crises.

Ramsey also observed that Middlebury's political climate made the talk feel less provocative than it might have in Hoover's usual Southern audiences. “He probably gets a lot more pushback [elsewhere] and therefore he might not have even understood that we had accepted to such an extent what he was saying, then looked for that next step.”

Earlier that day, Hoover had led a more technical faculty discussion. The afternoon lecture was intentionally designed to engage students from any major.

“The students here are way more engaged than a lot of places where kids are all just half asleep or fooling around,” Hoover said.

The annual series honors the late Professor David K. Smith ’42, a Vermont native, Navy veteran and Harvard-trained economist. He taught at Middlebury for nearly four decades, including 15 years as chair of the Economics Department. After his retirement in 1988, a lecture series was endowed to ensure an annual forum on applied economics.

Ting Cui '25.5 (she/her) is the Business Director.

Ting previously worked as Senior Sports Editor and Staff Writer and continues to contribute as a Sports Editor. A political science major with a history minor, she interned at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. as a policy analyst and op-ed writer. She also competed as a figure skater for Team USA and enjoys hot pilates, thrifting, and consuming copious amounts of coffee.