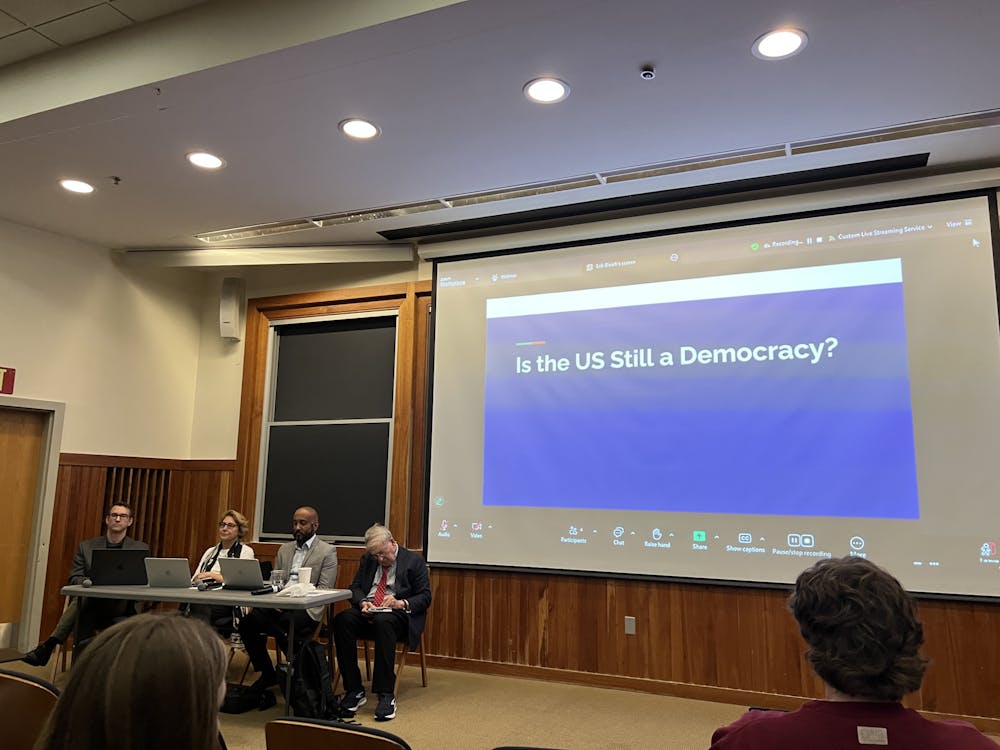

On Sept. 24, the Political Science Department hosted a roundtable discussion titled “Is the U.S. Still a Democracy?”. Professor of Political Science Erik Bleich moderated as Associate Professors of Political Science Sebnem Gumuscu and Ajay Verghese and Professor of Political Science Murray Dry provided their perspectives.

Bleich opened to a full room of students, faculty and community members: “What used to be unthinkable is now thinkable: that the U.S. is either no longer a democracy or will soon be no longer classified as a democracy by experts in this country and around the world. These are troubling times.”

He ended his introduction with a brief explanation of various forms of government and three stages of the move from democracy to autocracy: democratic recession, democratic breakdown and autocratic consolidation.

From there, Gumuscu and Verghese — both of whom specialize in comparative politics — defined democratic backsliding and gave historical parallels. Gumuscu likened the concept of democracy to a soccer game, with a level playing field, impartial referees, and evenly-matched teams. Democratic backsliding, she said, is akin to “tilting that playing field so that one of the teams has a higher chance of winning the game. And they keep winning that game because the playing field is no longer level.”

How does this happen? In the soccer analogy, it is ‘capturing the referees’ — in government, this includes civil servants, the Department of Justice and the judiciary.

“We’re seeing all the attempts on the part of the administration to replace some of these very important figures... they’re all very much deeply politicized as we speak,” Gumuscu said.

Verghese used his time to discuss the history of democratic backsliding and autocratic consolidation in former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s India in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. Initially thought by her own party to be “easily controlled,” she “gained control of the judiciary and politicized the civil service,” Verghese explained. After losing her role and being convicted of minor election crimes, Gandhi retook power a few years later with immediate retribution towards her opponents, limited media freedoms, and implemented a program that forcibly sterilized millions.

After suggesting parallels between Gandhi and President Trump, Verghese moved on to the resolution of the Indian case and what can be learned from that example. He articulated three points of action and focus, all based on his comparative analysis: voting, coalition building and selecting young, charismatic leaders. Verghese lastly emphasized the role of nonviolent protest, explaining how peaceful demonstration improves public opinion in opposition to an autocrat.

Dry focused more strictly on domestic politics: “I start not so much from the question ‘is America still a democracy?’ so much as ‘do we still have our Constitution?’”

He first made clear that we must recognize how a large portion of the country “supports, if not everything Donald Trump does, most of what he does,” then said that Trump’s actions have betrayed the conventions of American democracy, placing the onus on the Supreme Court for granting the president too much control over both domestic and foreign affairs.

After their statements, the panelists faced a handful of student questions, ranging from the appetite for political violence among young people to a post-Trump future of the MAGA movement.

Alpana Bakshi ’26 asked the session’s first question: “Has the authority overreached enough to mobilize the pushback?”

In response, the panelists put forth their ideas of what that pushback could look like. Dry put emphasis on the power of voting, attending town halls and speaking to representatives. Verghese restated the efficacy of “nonviolent disobedience,” including general strikes and economic boycotts.

In the crowded lecture hall, majors and non-majors alike, crammed side by side. Some students, like Gabe Palmer ’26, heard from professors in front of whom they sit in class every day. As a Political Science and Anthropology double major, Palmer was motivated to attend by the particular selection of panelists.

“Within the political science department, the question of ‘is America still a democracy?’ is discussed more by comparative professors. But given that Professor Dry was speaking, it seemed that the Americanist professors were more openly grappling with that question,” Palmer said.

Even for those less familiar with the department, the weight of the topic was clear. Hannah Gilmer ’26 said that she was motivated to attend the talk to “help situate what we see in the news in a broader context.” Like Palmer and Bakshi, she left the room with an appreciation of the variation in each panelist’s focus.

On the titular question, the panelists were mixed. While Gumuscu was unsure exactly how to classify the U.S., she said that “we passed the threshold, for sure. This is not a liberal democracy. This is not perhaps even an electoral democracy.”

She expressed disappointment in non-governmental actors who are “not doing a good job” in the face of backsliding.

“That’s very concerning to me because there is no united force yet that is mobilized against these attacks against American democracy,” she said.

Verghese first agreed with Gumuscu: “I would also say deeply concerned.” He warned against predicting the political future, but again used the Indian case as an example, where Gandhi’s overreach led to a “self-correcting” response, with people pushing back to federal overstepping.

Dry was hesitant to classify the U.S. as anything other than a constitutional democracy — at least so far. In his closing remarks, he clarified that “I think that this individual, in the office he holds, given its power, is a threat to the constitutional rule of law.”

Editor’s Note: Senior News Editor Cole Chaudhari ’26 contributed reporting to this article.