Four years is a pitifully short time for something so blatantly, absurdly wonderful: being an undergraduate on this campus. It would be remiss of every Middlebury student to take for granted the fact that everyone they know is within a 15-minute walk. It would be remiss to forget that the gym, the ice rink, the tennis courts, the pianos, the computer labs, and all the camping equipment you could ever need are all universally accessible — and free. It would be remiss to forget that, if you are on the dining plan, you could eat eight completely different meals a day without ever driving to the grocery store or spilling a single bubble of dish soap.

And, for all this, we are obliged only to readings, problem sets and attendance in class, the latter of these often contingent on whenever we decide to call in “sick”. These academic items are highly curated, often world-class: dozens of brilliant people have dedicated their whole lives to ensuring that these things are as good and useful to us as possible.

We have the responsibilities of children and the privileges of kings. Most of us will not savor that we are the royalty of Candyland until we taste the bitter pill of the nine-to-five. You could almost argue that the high quality of life at Middlebury is so out of proportion to the real world that it is an act of cruelty to let anyone experience it.

It takes a considerable feat of imagination (and maybe a little ingratitude) not to love Middlebury for these reasons alone. If you really take a moment to consider these aspects of our lived experience — many of which are so quickly and deeply invisible to us — it seems criminal that students could be encouraged to study abroad. How anyone could spend a semester or even a year away from this of their own volition is truly beyond me.

Of course, many do. But only some for good reason. The only argument I can get behind is language acquisition: the only way to learn a language is to live it. If your intention in college is to acquire this mastery, I agree that you basically must go abroad in a full-immersion program — and commit to it.

It is true that some English-speaking abroad programs are quite academically demanding. But some are not. Some are so undemanding that the opportunity cost of missing just four normal Middlebury credits is eye-wateringly disproportionate. At Midd we are offered access to world-class academia; if you’re going abroad for the academics, you might be leaving Eden in search of greener pastures. And if you’re not… why are you going at all?

The truth of the matter is that going abroad is supposed to be an extreme. Abroad, on paper, functions for a small minority of students with outsized academic needs. But it has become “la mode” for Junior classes to fracture into six-month vacations, right at the intended peak of their social and academic lives. Going abroad might overwhelmingly be the wrong choice for most students, yet it has practically become the dogma of our collegiate times.

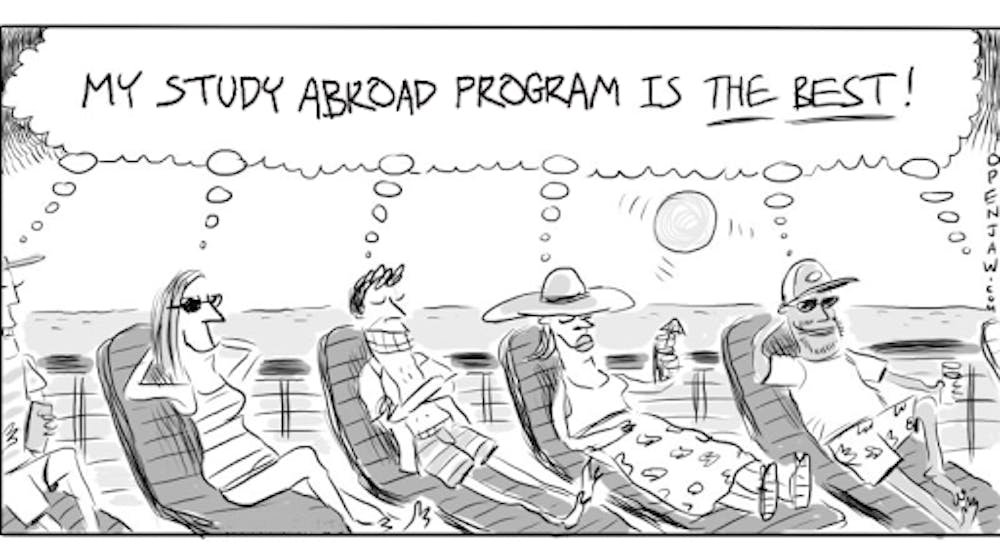

Let’s not beat around the bush here. What are some of us really doing when we’re abroad? Are we really learning Dutch? Perhaps we’d all prefer to think so, because I don’t know what else could justify some of these bon-vivant vacations. All of us can think of one friend who came back from Europe with nothing to show for it beyond an admirably extensive survey of the local pub scene.

I can’t speculate as to how this happened, but I must question our tolerance to its detrimental effects. Why do we simply accept as a fact of college that Junior year is a social dead-zone? Why do we so easily overlook the jarring discontinuity — discontinuity in classes, clubs, sports, relationships, virtually all facets of the Middlebury experience — that is directly, needlessly inflicted by the abroad cycle? We love to lament about the loss of community, yet we are all too eager to ignore the study abroad frenzy as a probable cause.

These issues are entirely preventable by a simple paradigm shift: Most students should not randomly adjourn their preciously short college experience to go sit in an apartment in some foreign city.

Is it really so controversial to suggest that most students would be better off staying in Middlebury, furthering the communities they have spent the last two and a half years working a foothold in? Instead they find themselves carted onto airplanes, returning home six months later — often dissatisfied, and usually having discovered the same appreciations that I have freely outlined for you in the beginning of this article. This appears to be such a fool’s errand that you might begin to speculate who, if not students, is really benefitting from abroad programs…

Don’t confuse my point: there’s nothing wrong with drinking in European bars. Admittedly, it could even be a life’s calling for most of us. But we have approximately 60 years to answer life’s calling after we graduate, and we only have four years here, four years to learn, mingle and play. Weigh the numbers however you want.

If you agree with me that our basic luxuries here are, in many respects, “all one might ever need”, you will agree that our time here is extremely valuable and worth appreciating, especially because it is so blindingly short. This, to me, is the overwhelming case against studying abroad. Not because the world isn’t interesting, but because the world is not going anywhere. But Middlebury will, and once it’s gone, it’s gone for good.