Vermont is weighing a controversial plan to trap and remove beavers from 21 state-owned dams in order to mitigate blockages and ensure infrastructural integrity.

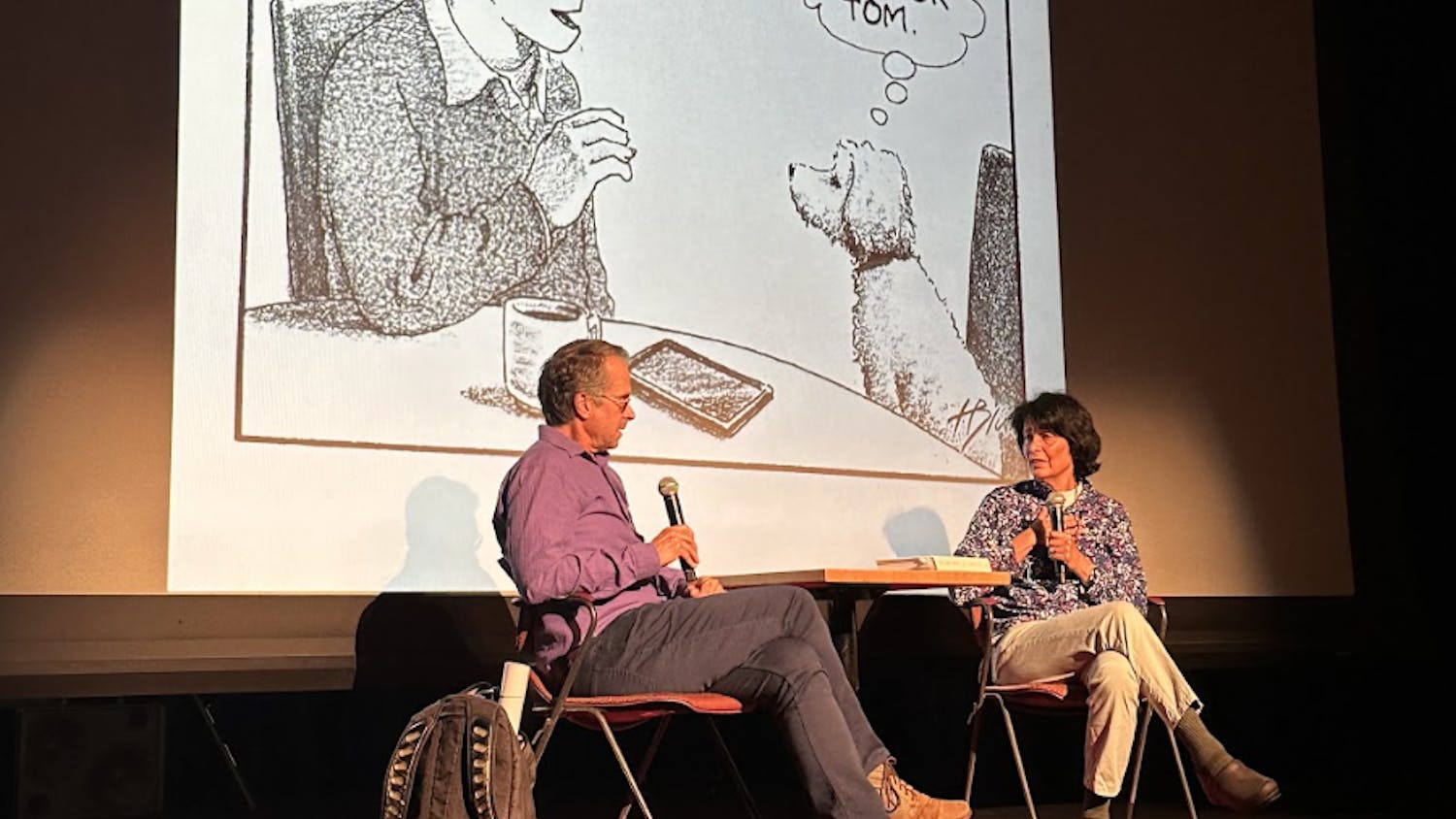

The Vermont Department of Fish & Wildlife hosted two public information sessions in Montpelier, Vt. and Middlebury last week to share their plans with the public. Attendees questioned the state’s intention to move forward in removing the beavers without further community input, while others pointed to non-lethal methods that may be more cost-effective and practical than traps.

Representatives of the state have said that the roughly 100 dams owned by Vermont’s Agency of Natural Resources would be affected by new rules created in response to Act 161, which passed in 2018. The Department of Environmental Conservation says the law requires the agency to address dam safety by modifying the structures, trapping and killing nearby beavers, or removing the animal’s debris.

“Beavers are a keystone species,” Bree Furfey, a wildlife biologist with Vermont Fish & Wildlife said at the meeting on April 10. “They can create these wetlands that are actually homes for several other different species, and so they really help to create biodiversity.”

Despite their ecological benefit, the state has identified trapping and killing beavers as the only effective remedy to prevent beaver-induced build up around Vermont-owned dams that it says causes excessively high water levels, potentially contributing to floods. Affected areas under the current plan will include the popular Bristol Pond in Monkton, Vt.

Several officials from the department shared that modifying state-owned dams would have to be a long-term consideration due to the high costs associated with any changes. Representatives stated that short-term options of inaction, relocation and regularly removing debris would not address the problem, although they left the idea of modifying the dam structures open for future consideration.

“There are options there, we just have to come up with the money and as the estimates go, it's only going to get more and more expensive,” explained David Sausville, a wildlife management program manager who spoke at the meeting.

Beverly Soychak, co-founder of the Vermont Beavers Association — an organization which aims to educate people on non-lethal beaver management — said she was disappointed by the state's approach to managing its dams after attending the public information meeting in Middlebury.

“I think there’s some false information that was shared out at that meeting about beaver deceivers and their efficacy,” Soychak told The Campus in an interview. “We have to do what Vermonters want to do, not what Fish and Wildlife wants to do. They haven’t even looked at other solutions.”

Beaver deceivers are a non-lethal device made by a company based in Grafton, Vt. that can be installed in dams to allow water flow and promote biodiversity without disrupting beavers’ ability to thrive in Vermont’s waterways. Officials at the public information meeting had previously panned beaver deceivers as a possible long-term solution to modify state-owned infrastructure.

“When you start getting some inflow and you need to get that water out, that’s when the beaver deceivers and those kinds of techniques are not as effective,” Steve Hanna, a dam safety engineer with the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) said at the meeting.

Skip Lisle, the founder of Beaver Deceiver International Co., said that he was concerned beaver deceivers were being maligned by the proceeding, since he has successfully used the deceiver on man-made dams, contrary to what the state has suggested.

“Beaver deceivers are unique to my company, and it does a lot of harm to tell the world inaccurately that they do not work at man-made dams. I’ve used them at hundreds of work sites around the country,” Lisle said at the meeting. He added that the state should use the terms flow device or baffle instead of beaver deceiver in its work and presentation.

Soychak said she worried the recent spate of flooding that devastated Vermont in the summers of 2023 and 2024 have unfairly led to scapegoating beavers for flood damage.

“It’s my personal belief that the flash flooding has brought this issue to the forefront the past two years,” Soychak said, adding that removing beavers will not be a long-term solution to safeguard against flooding. “If a flash flood is going to take out a mountain, how is a dam ever going to stop it?”

She added that in Monkton, Vt., where she lives, local dams have seven beaver-deceivers and did not see catastrophic flooding the last two summers.

Another audience member who spoke at the meeting said he believed the state should sell licenses to local trappers for the beavers on the dams, providing a potential revenue source for the state.

“That’s a cost-generator that could replace the cost of my tax dollars,” he told the group. “If we’re short on cash, why not get paid by someone to solve the problem instead of paying somebody to get rid of the problem?”

His idea was not echoed by other people in attendance at the meeting, who were largely against lethal trapping methods.

“What measures are going to be taken so that recreators and their animals are not going to be harmed or caught in its traps?” a third audience member asked.

Fish & Wildlife and the Agency of Natural Resources did not answer these questions asked by attendees; the third-party moderator instead wrote them down to be answered in two months via a written report. The moderator also corrected people who offered statements rather than asking questions during the forum on Thursday.

“These were public information sessions and not official public meetings. Staff will review and respond to the public’s questions in a responsiveness summary, but feedback will not be incorporated into the Dam Safety Rules,” Stephanie Brackin, communications director for ANR wrote in an email to The Campus.

Audience members expressed frustration with the meeting set-up, which they felt deflected responsibility for the changes from the Department of Fish & Wildlife.

“The bottom line is I don’t think that was a democratic process,” Soychak explained in an interview. “This was Fish & Wildlife’s way of not listening to the other side of the debate.”

After The Campus provided a list of questions to Vermont Fish & Wildlife related to beaver management, a program manager at the department sent an email that the agency members needed to coordinate their response on the matter to ensure consistent messaging to the public.

“These are the same questions asked as the meeting and I want our response to be the same as our summary document. We don’t need them playing slight word changes against us,” the staff member wrote to everyone included on the email.

Following that message, Furfey declined to comment to The Campus, stating that she could not answer questions in a timely manner without consulting the Vermont Department of Environmental Conversation (DEC).

“In general, Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife strives to have a healthy beaver population… which [the] habitat can support and what the public will tolerate,” Furfey wrote. “The DEC rule is strictly at manmade dams. This will not impact the state’s beaver population.”

While the state continues to move forward with its plan to trap beavers, local environmental advocates urge them to reverse course and engage with criticisms of the lethal population control methods.

“We want to bring the temperature down and work together on this, because that’s the only way this is going to get done,” Soychak said. “Some really tough conversations need to be had, and we’re not getting that right now.”

The Vermont Department of Fish & Wildlife has said it will release a “written responsiveness summary” responding to the solicited questions by June 1.

Ryan McElroy '25 (he/him) is the Editor in Chief.

Ryan has previously served as a Managing Editor, News Editor and Staff Writer. He is majoring in history with a minor in art history. Outside of The Campus, he is co-captain of Middlebury Mock Trial and previously worked as Head Advising Fellow for Matriculate and a research assistant in the History department. Last summer Ryan interned as a global risk analyst at a bank in Charlotte, North Carolina.