Author: Kate Prouty

Are a drunk and desperate doctor, an 18th century seductress and a stripper the best people to give love lessons?

Maybe not in the traditional sense, but they can teach at least one truth: love is a deceptive, ambiguous and unreliable riddle. Although these three seemingly unrelated characters were among the revealers of this reality in the Hepburn Zoo's "Disarming" last weekend, they had in common at least one tragic flaw: they were human. Because they were human, they were victims.

They were victims of seduction, passion and deceit, but most of all, they were simply victims of human emotion. Whether it was in 18th century France or contemporary America, the play's wide range of character types suggested that everyone is vulnerable to the turbulence that love leaves in its wake.

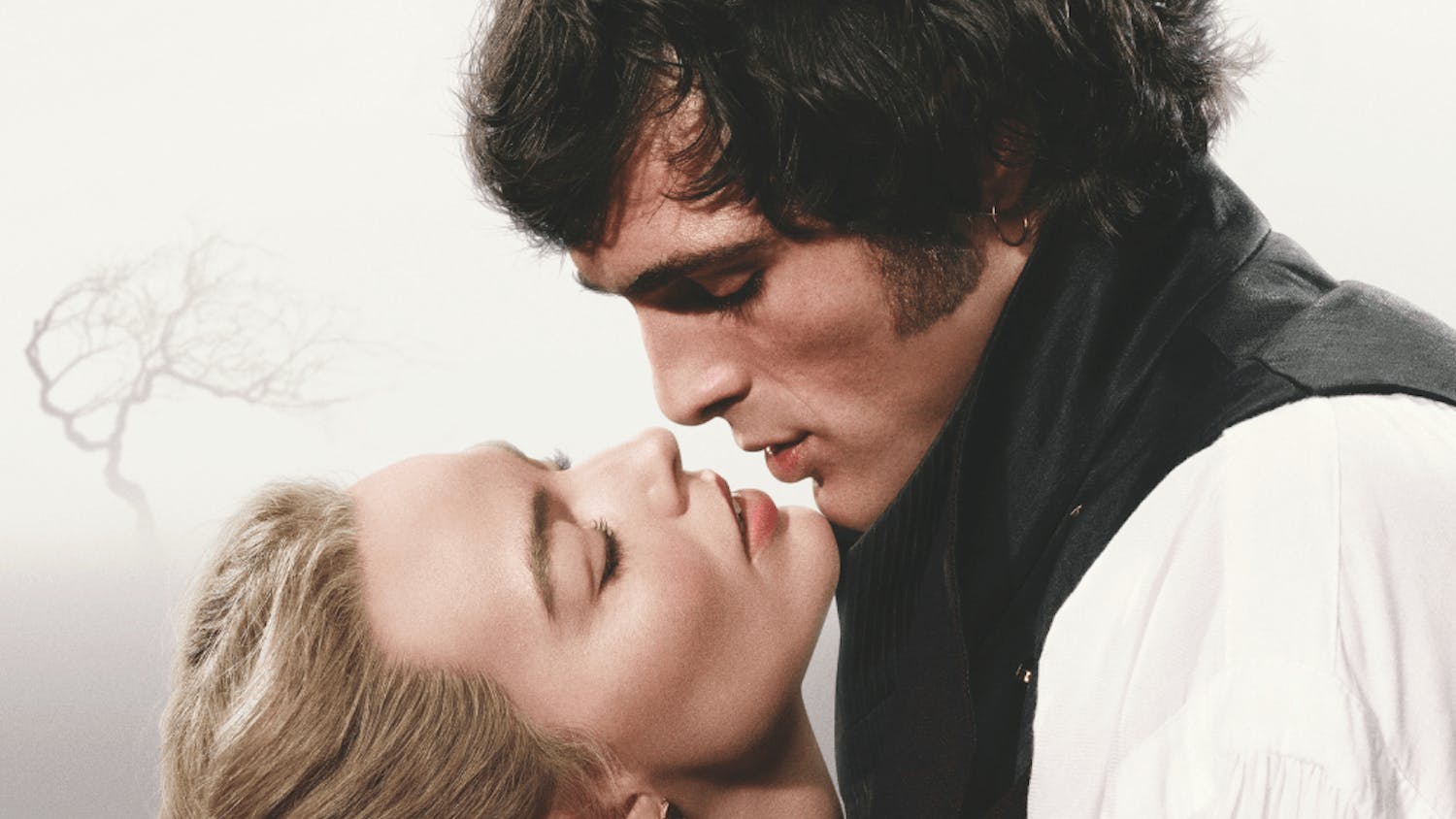

This was the thematic thread that wove together the stories of "Dangerous Liaisons" (Christopher Hampton's 1987 theatrical adaptation of Choderlos de Laclos' 1782 novel "Les Liaisons Dangereuses") and Patrick Marber's modern play "Closer" into one whirlwind of intensity that was, as its title promised, disarming.

By carrying the weight of these three historically distant titles, the play aimed to span centuries of creative focus and shifts in societal makeup. And yet "Disarming" successfully dissolved the boundaries of the historical gap by focusing on the universal and timeless truths of relationships.

Directed by Jesse Holland '01.5 and Jacob Studenroth '03, the play was structured in ten chunks of fragmented story line, switching consistently back and forth between a scene from "Dangerous Liaisons" followed by a scene from "Closer."

The transitions between these scenes were quick and required that the actors, three of whom had roles in both plots, adjusted their costumes on stage in the dark to suit their fluctuating roles.

Unfortunately, the costumes did not add as much to the production as did the well-executed acting. Due to limited resources and the necessity of rapid costume changes, Maria Ostrovsky '02 admitted that the lack of clothing options was frustrating, but unavoidable. Originally she and Nicholas Vail '02, who both received credit for senior work on the play, had visions of white wigs, ruffled shirts under suit jackets and grandly layered hoopskirts to portray the opulence of "Dangerous Liaisons." Although this goal was unachieved and the role of the costumes was thus downplayed, they managed to work, and work well, with what they could find.

As quickly as they shed a skirt or a jacket, Ostrovsky and Vail also had to instantaneously adapt their attitude, vocal intonation and movement to represent their character.

Ostrovsky's roles were especially dissimilar, transitioning from the seductively cruel Marquis de Merteuil in "Dangerous Liaisons" to the "disarming" stripper Alice in "Closer." Vail also had some emotional adjusting to do between playing Merteuil's sexual conquest counterpart and the slightly insecure obituary writer Dan, who falls in love with Alice when he brings her to the hospital after she is hit by a taxi.

Nick Bayne '02.5, although appearing only briefly in one of the last "Dangerous Liaisons" sections, brought humor and raw emotion to "Closer." He plays Larry, a doctor who offers his patient Alice a cigarette and then later, in a drunken plea, begs for her companionship while he ogles her in a strip club. The desperate desire to connect with someone emotionally, which Bayne delivered convincingly, ironically overpowered the typical sexual arousal associated with a strip club.

The energy in the two plays was so drastically different that Ostrovsky and Vail opted to rehearse them separately at first, in order to fully develop each character within its appropriate context before juxtaposing it with another world. After they fleshed out the motivations for each character, they eventually wove the scenes together into the collage.

Ostrovsky and Vail originally intended to work only with "Closer," but after casting complications, shifted their focus to "Dangerous Liaisons." Too dense to consider alone, they decided to present it as a partner to "Closer." The decision to link the two works was smart and truly poignant. Although in years they are worlds apart, both plays share themes and even vocabulary.

As Suzanne Weiss points out in a CultureVulture article, "['Closer'] is no Victorian drawing room drama. Yet the dance of two couples — each in love with a significant other, yet drawn to the other's other — has all the elegance of an 18th century gavotte."

Having the same actor play a role in each play reinforced this connection.

Senior Joe Varca's set and lighting design dealt well with the limiting space of the Zoo. Hanging metal poles surrounded the audience, renforcing the coldness of failed intimacy while also extending the space vertically to reflect the extravagent wealth of the "Dangerous Liaisons" scenes.

As lovers in each play coupled and uncoupled in this dance of emotional destruction, it became glaringly obvious that nobody was going to come out on top.

Dan's concluding monologue implied that love is a fragile and false thing because it dupes even its most loyal believers under false pretenses. Alice said she fell in love with Dan because he cut the crusts off of his bread. In his closing scene, Dan admitted that he only cut the crusts off his bread that one day because they were crumbling in his hands.

Crusts or not, "Disarming" was attuned to the cruel injustices of love spanning centuries of intimacies.

'Dangerous Liaisons' Exposed by 'Disarming'

Comments