In retrospect, it makes peculiar sense that, of all contemporary American directors, Paul Thomas Anderson would prove best-equipped to make the decade’s first great “Movie About Our Times.” The cokey, affecting mania of his early films (“Magnolia,” “Boogie Nights”); the strange, libidinal inexplicability of his later ones (“Phantom Thread,” “The Master”); and the unabashed, operatic clamor of his big one (“There Will Be Blood”) are united in his latest project, “One Battle After Another,” which meets the manic, inexplicable, clamorous American moment without indulging in its stupidity or endorsing its fatalism. Anderson has never set a movie in the present, but, in a way, it’s as if he’s been preparing to all along.

One hallmark of any Anderson movie is a certain tonal fission, a tipping of the narrative dominoes that leads the audience from an initial, straightforward emotion to a compounded one somehow more lucid for its electric confusion. Anderson can make the move within a single scene (see: Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s character breaking down after trying to impress Mark Wahlberg’s with his new car in “Boogie Nights”), or it can feel as if he’s making it over the course of an entire movie (see: “Magnolia”). The impulse to open not just one, but several, tonal floodgates, and then to ride the current for longer than expected, is what most animates his films — even “One Battle After Another,” his first real popcorn thriller. To laugh when you probably shouldn’t (or vice versa), to not know whether what you are watching is deadly serious or absurdly unserious (or both) — what could be a more fitting effect for a movie about today’s political climate?

Without such a restlessly imaginative, typically atonal score from Radiohead guitarist Johnny Greenwood — who has worked on Anderson’s last six films — it would be hard to make the tonal bedlam of “One Battle After Another” work. The music is the stitching that holds the film together, enabling the rage of one scene to fuse with the delicacy of another, the desperation of one with the melancholy of another. In hindsight, the incredible scene in “Magnolia,” in which the film’s main characters break from reality to sing Aimee Mann’s “Wise Up,” looks like a breakthrough in Anderson’s understanding of how music could serve his directorial ethos: eight characters in different places and different situations, but all somehow connected to one another, tuned in to the same psychic FM station on which Mann is being played. What Anderson did with the scene was new, but the headier idea it expresses — that personal experience is not relegated to the singular self, that what happens to anyone is also happening to you — is as old as art.

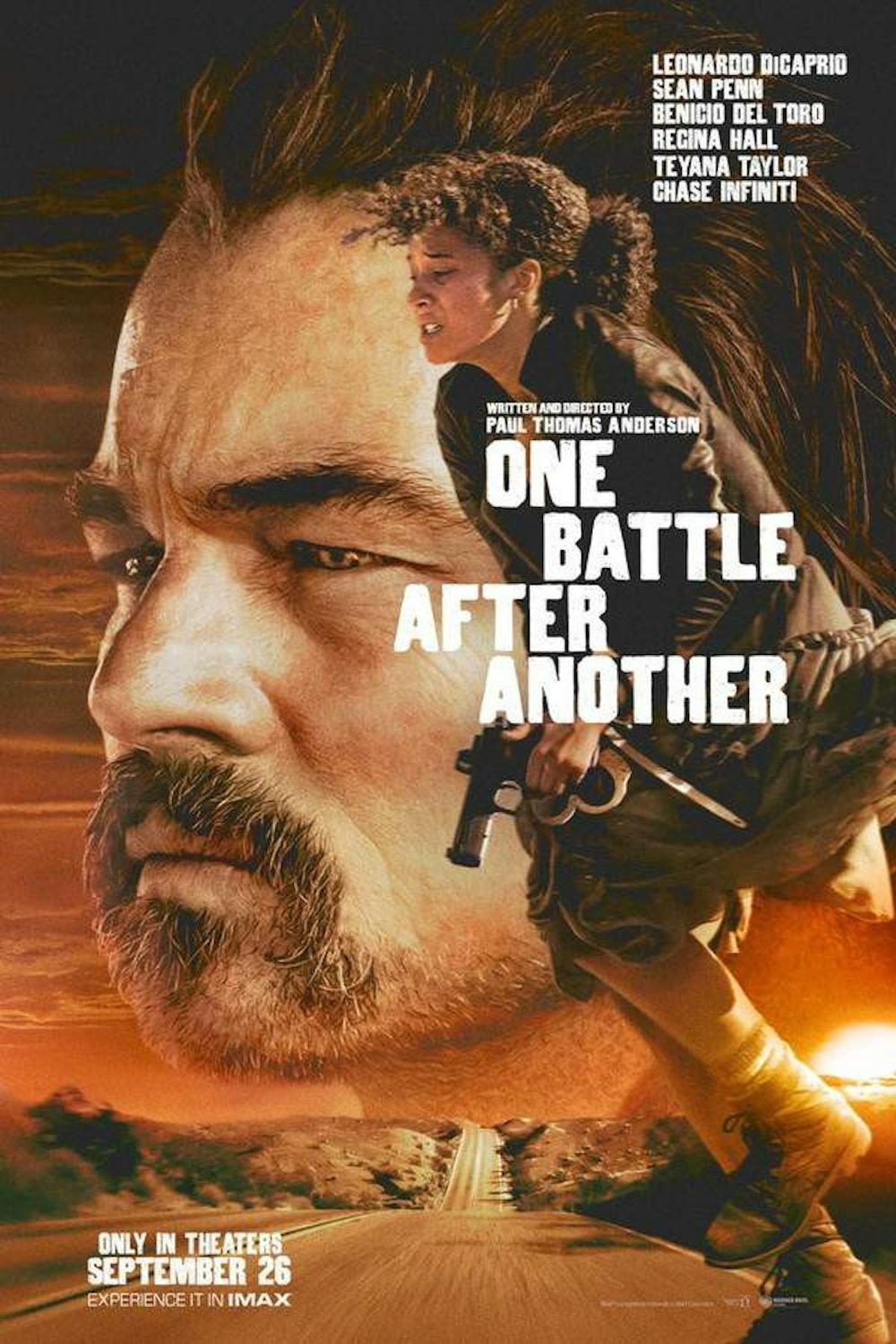

The exact politics of "One Battle After Another" has been a source of some confusion. It seems unclear to a number of critics — conservative and left-leaning alike — that the movie is not a total endorsement of the kind of radicalism practiced by some of its main characters. (Leonardo DiCaprio’s and Teyana Taylor’s characters are members of the group “The French 75”.) The National Review’s film critic Armond White, for example, writes that Anderson “romanticize[s] Sixties political violence” in a “cowardly artistic choice.” He likes the part where DiCaprio’s character settles into the couch with a joint, mouthing a credo he no longer has the energy to live out: “The most politically astute scene shows a pothead radical getting stoned while watching ‘The Battle of Algiers.’” But isn’t that the point? What Anderson is being astute about is the fact that many former radicals had fun being dangerous in their twenties and then retreated into selfish cynicism in middle age.

In fact, DiCaprio’s character — who White reads as “woke-before-woke” — endangers the entire project of another character, played by Benicio Del Toro, who is actively protecting dozens of lives in what he calls a “Latino Harriet Tubman situation.” Del Toro’s resistance to the state is of the unshowy variety; DiCaprio’s was always more about the explosions.

Might part of Anderson’s commentary, then, be about how woke actors sometimes hamper one progressive cause or another, getting in the way of people who know what they’re doing but are less interested in the posturing? More partisan-minded critics have tried to either indict or champion the archetype represented by the movie’s revolutionaries. But the movie doesn’t do only one.

Who Anderson does indict (those intrigued by fascism and ethno-nationalism) and champion (a Gen Z character, played by Chase Infiniti, mired in the mess her elders have made of her life and country) is clear. At one point in the movie, Infiniti screams, while holding a gun to her own father, “who are you?” It feels, by then, that Anderson has made one of the most sympathetic movies to Gen Z’s existential predicament yet.

One can argue the specifics of the movie’s politics and, so long as you don’t find it “openly seditious,” like White, still respect Anderson’s will to make a movie that is political at all. Recently, that will has been lacking, not just among American filmmakers, but among writers and musicians, too. The problem is not distinct to our time. As Phillip Roth wrote in a 1961 essay for Commentary titled “Writing American Fiction,” “the American writer in the middle of the 20th century has his hands full in trying to understand, and then describe, and then make credible much of the American reality. It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meager imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents.”

Countless articles have articulated similar concerns since the beginning of the Trump years (“Is Satire Dead?”, etc.), and certainly the absurdity of our decade outdoes that of the sixties on multiple fronts. So Roth’s concerns for his own time feel doubly dire when applied to the context of our own: “Much has been made, much of it by the writers themselves, of the fact that the American writer has no status and no respect and no audience: the news I wish to bear is of a loss more central to the task itself, a loss of subject ... a voluntary withdrawal of interest by the writer of fiction from some of the grander social and political phenomena of our times.”

This, it seems, is the central question for American artists working today: Will they back away from the moment, or step towards it? In a film industry still dominated by Marvel-like franchises — whose culture consists largely of, as Marc Maron put it, “grown male nerd children” — it is reassuring to see a great director do the latter: find the subject his medium has been losing.