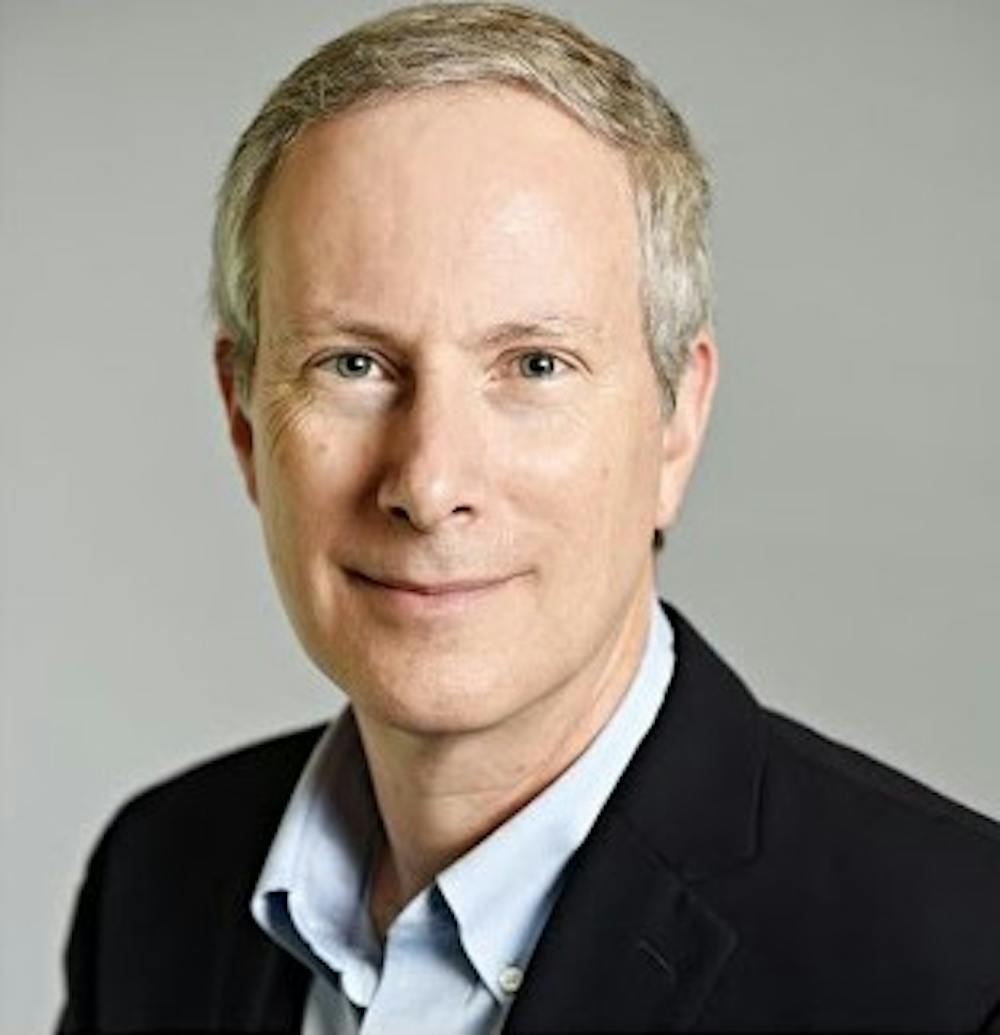

Director of Harvard’s Center for Jewish Studies Derek Penslar gave this year’s Hannah A. Quint Lecture in Jewish Studies, titled “The Struggle for Palestine on the World Stage, 1947–1949.” As Harvard’s William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History, Penslar studies Jewish history within the contexts of modern nationalism, capitalism and colonialism.

He spoke to an audience of over 50 Middlebury students, faculty and community members on Thursday, April 17 in Twilight Auditorium. Beginning in 1988, the annual Hannah A. Quint Lecture was by Eliot Levinson ’64 in honor of his mother to “provoke interest in and to deepen understanding of the culture, the religion, the history, and the literature of the Jews, and to bring a Jewish perspective to bear on ethical and political questions.”

Penslar began by posing questions for his audience: Why Israel? Why does it attract so much attention and passion? Listing examples, he probed at the lack of widespread awareness of other conflicts in the world.

“What about Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or Syria?” Penslar asked. “Palestinians are not the only people to be displaced.”

He then compared the current pro-Palestinian movement across college campuses to the Vietnam anti-war movement. Despite there being no enlistment of American troops for Israel, Penslar noted that college students express similar passion for Palestine as past generations did for Vietnam in the 1960s.

Reframing his own questions, Penslar stated that the answer to why this is is not obvious, nor is antisemitism the main or sole factor for this focus on Israel. Instead, he said the answer lies in thinking of the long-term historical conflict of Israel-Palestine as a lightning rod for anti-colonialism, anger and Holocaust guilt.

Through a series of primary sources from past government officials and popular news media, Penslar analyzed attitudes toward Israel among governments, media organizations and the public in Asia, South America and Europe. Concentrating on 1947–1949, he showed reactions to the surge of Zionism, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the formation of Israel from 1947–1949.

Penslar also examined Arab nations’ response to the establishment of the state of Israel as seen in the Middle East and South Asia. He walked through how those regions saw emerging demands for a constitutional Arab state for the Palestinians. For many Arab nations, according to Penslar, Zionism was seen as an extension of British and American colonial expansion.

Penslar also spoke about how Arab calls for Palestinian nationalism were supported in South Asia, where fears and skepticism towards partition stemmed in part from the 1947 British partition of Pakistan and India. Because this support for Palestine stemmed from the violent population transfer that occurred under the partition, Penslar noted South Asian rhetoric was mostly free from antisemitism.

Europe’s role in the genocide of Jewish people during the Holocaust also shaped certain reactions to Zionism. For some, that led to the desire for forgiveness of Holocaust guilt and served as a new direction of antisemitism, both among groups opposing a Jewish state and among those still looking to expel Jewish populations from their borders.

Penslar’s final analysis centered on Latin America and its unique relationship with Palestine. Because of the geographical distance between the two regions, Penslar pointed out how Latin America has less direct involvement in the reconstruction of a post-Holocaust world. Zionist political organizations, called pro-Palestine committees in reference to the land itself, are somewhat prominent in Latin American countries.

However, Penslar also underscored Latin America’s animosity towards Britain because of previous informal colonial projects. Enclaves of Arab and Palestinian immigrants who sought refuge in South American countries were thus able to successfully lobby their governments to support the Palestinian movement. This resulted in many Latin American governments abstaining from voting on the British-backed partition.

Following the lecture, Penslar opened the floor for questions from the audience.

The first question remarked on the lack of anti-Arab sentiment presented as a motivator for the Jewish violence and resulting displacement of Palestinians in 1948.

In his response, Penslar mentioned anti-Arab racism present in the Zionist movement and also added that some voices sought coexistence between Israel and Palestine.

Another series of questions asked Penslar about his historical evidence for the claim that a two-state solution would be effective or possible.

Penslar stated there is no guarantee of a reasonable outcome, as historical evidence suggests the high likelihood of unrest in both outcomes, partition and a multicultural federation.