JAMES FINN

Jackson's Women's Health Organization, the last open clinic to provide abortion care in Mississippi.

Jackson's Women's Health Organization, the last open clinic to provide abortion care in Mississippi.

As Middlebury students hunkered down in the library to work on final exams this May, state lawmakers were gearing up to put Roe v. Wade to the test.

Nine southern and midwestern states captured national attention for passing a wave of abortion restrictions. Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, Kentucky, Louisiana and Georgia all approved bills that would ban abortion once a fetus has a detectable heartbeat. Arkansas and Utah voted to limit the procedure to the middle of the second trimester.

Alabama’s governor signed a near-total ban on abortion on May 15. The ban would allow no exceptions in cases of rape and incest. Alabama doctors who administer abortions could face up to 99 years in prison if the law goes into effect in November, after a six-month waiting period following the bill’s signature.

At Middlebury and other colleges around the country, students reacted publicly and emphatically. Amidst finals week stress, students shared testimonials and action guides on social media, discussing the implications of the new laws. The news hit particularly close to home for students from affected states.

“This took place over finals for me and it was a surreal moment in time,” said Holley McShan ’19.5, who is from Alabama. “The rage it sparked made it difficult to think about anything else.”

Worlds away from home

That week in May exemplified why many students from the South, where the most restrictive abortion laws were passed, grapple with their relationships to home. Southern states are often maligned by progressives in other parts of the country as trailing years behind states like Vermont — which recently codified protection of abortion rights under state law* — when it comes to women’s rights, abortion access and race relations.

When non-southerners at Middlebury voice these criticisms, some southern students find they miss the mark on how these issues manifest at Middlebury and their own homes. Jess Garner ‘19.5, who grew up in a suburb of Jackson, Mississippi, said they have always felt the need to defend Mississippi to non-southerners at Middlebury.

“The worst part is the incapacity of some people to realize how much the liberal or centrist bubble of their upbringing has taught them to scapegoat the South, while ignoring the same problems in their backyards,” Garner said.

When news like Alabama’s near-total abortion ban reached campus, southern students said peers from elsewhere were quick to condemn their home states.

“This spring, I saw peers saying that we should just ‘cancel’ Tennessee,” said Sophie Swallow ‘20.5, who is from Sewannee, Tennessee. “What does that do? What about all the people working for change? What about all the people in need? It’s easy to criticize Tennessee, but it’s harder to go and try to make change.”

Martha Langford ‘20, who is from Jackson, said news of Mississippi's restrictive abortion law reminded her of how isolating it can feel to grapple with such news among people who don’t fully understand what’s at stake in her home state.

“I feel exhausted by the odds stacked against economic, racial and reproductive justice in Mississippi, and I often feel alone in this exhaustion at Middlebury,” she said.

Dani Skor ’20 grew up in Clayton, Missouri, a town in St. Louis County. St. Louis is home to the widely-publicized last clinic in Missouri still able to provide abortion care in the state. A sense of pride for St. Louis has been a central part of her identity at Middlebury, but she has felt the need to reconcile that pride over the past two months.

“I felt like I needed to separate myself from my home, and that hurt,” she said. “Since the law passed, I've realized that just as I can love a family member or a friend who has different opinions than me, I can be pro-choice and still love and take pride in my home state.”

Skor said that watching the news unfold from her study abroad semester in Italy was isolating and made her homesick. Swallow watched the news of Tennessee’s restrictive law — a “trigger law” signed by the state’s governor on May 10 that would ban abortion there if Roe v. Wade were overturned*— unfold from Guatemala City. She has spent the past year there working with an organization that provides contraceptives and sex education to young women.

“Being far away made me forget about the power of conversation and that minds in Tennessee can be changed,” Swallow said.

COURTESY IMAGE

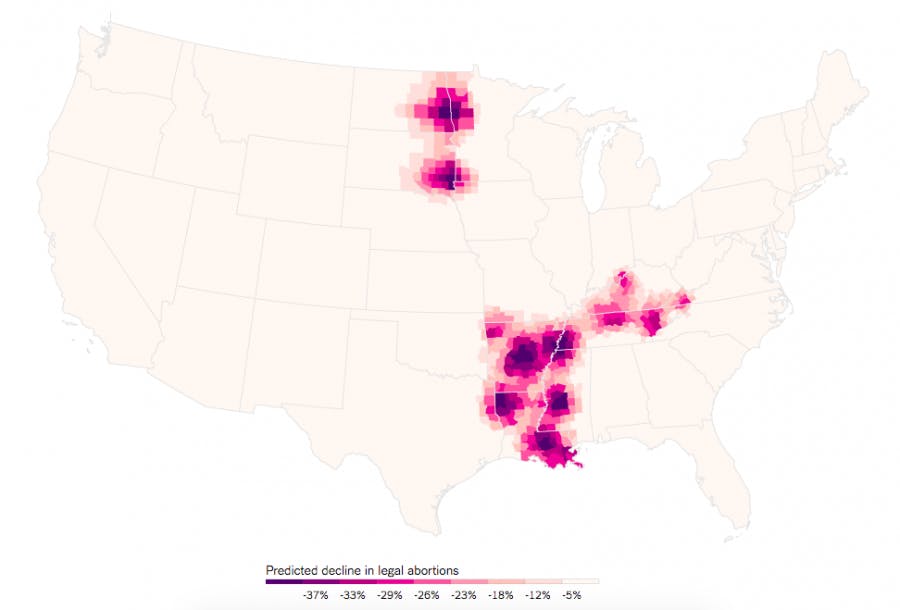

According to a New York Times article, the number of legal abortions would fall in these places if Roe v. Wade were overturned.

According to a New York Times article, the number of legal abortions would fall in these places if Roe v. Wade were overturned.

Closed-door clinics

Abortion remains safe and legal in the nine states that passed restrictive abortion laws in May, due to waiting periods that separate law signage and implementation.

Court battles over the laws’ constitutionality may hold implications for the future of Roe v. Wade. Certain extreme abortion bans, like the one signed in Alabama, were written with the intent of provoking lawsuits that might eventually result in a Supreme Court battle over Roe.

If Roe does fall, 21 states are considered at risk of banning abortion outright.

A recent study headed by Middlebury Economics Professor Caitlin Myers predicts that, in a hypothetical “post-Roe” scenario, the average woman in affected areas — places where travel distances to nearest clinics are expected to change — will experience a 249-mile increase in travel distance to nearest abortion clinic.

Myers grew up Burnsville, West Virginia and LaGrange, Georgia. While analyzing data from the Abortion Facilities Database for her study, she looked at what a post-Roe landscape would mean for her hometowns.

If Roe were overturned, she said, West Virginia’s only remaining abortion clinic would close, and women in Burnsville would have to travel 170 miles to Pittsburgh to access the medical procedure. She estimated that 20% more women would be unable to reach an abortion provider with this increase. That number would be even higher — around 33% — in LaGrange.

“As an empirical economist, my job is to identify, measure and understand causal effects, not to tell people how I feel about them,” Myers wrote in an email to The Campus. “But as a native of Appalachia and the deep south, I do sometimes look at what the results say about my hometown … Roe matters a lot in the places I’m from.”

Students like Langford, McShan and Swallow recognize that their privilege gives them an advantage in retaining opportunities for care as their states restrict abortion access.

“I’m grappling with the fact that I have enough privilege that, if needed, I’d likely be able to get around these bans and still have reproductive autonomy,” McShan said.

Langford said she grew up recognizing that if abortion completely disappeared from Mississippi, she would still have a much easier time accessing care than poor and black women who live in rural areas of the state.

Her feeling of safety shifted in high school, when she realized that the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a low rose-colored building in Langford’s neighborhood, is the last open clinic to provide abortion care in Mississippi. The other remaining clinic closed in 2006.

For Langford and other pro-choice Mississippians, the Pink House represents both hope and anxiety for the state’s future. Simultaneously, the constant possibility of losing the clinic in the face of new regulations brings a fear that this beacon of hope for Mississippi’s future could quickly be dashed.

“I wonder how many other students at Middlebury are limited to hope in a singular pink building,” Langford said. “I don’t know if people in more progressive and affluent states share that kind of political anxiety.”

* Corrections: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the bill guaranteeing legal access to abortion access in Vermont. The bill was passed as a state law, not a constitutional amendment.

Additionally, an earlier version of this story erroneously referenced a “fetal heartbeat law” that passed in Tennessee’s house of representatives in March, then fell before its senate. The legislation that Swallow referenced was a different piece of legislation — a trigger law that passed in May.

Comments