When the op-ed “It’s Actually Just a Game” was published in the Campus on Jan. 22, what followed was an explosion of conversation about athletics on campus. With almost 60 comments online and multiple responses to the opinion piece, the topic dominated conversations until the end of Winter Term.

In light of this, the College has been forced to consider a divide between the athletes and non-athletes on campus. This divide has given rise to a number of questions surrounding the role of athletics at a school like Middlebury and the existence of athletic privileges.

As a member of the NCAA and NESCAC divisions, the College athletic department abides by two sets of rules, both of which strive to create an athletic environment consistent with a commitment to academics. However, as the College and so many other institutions have discovered, finding the right balance between athletics and higher education can be difficult.

The NESCAC established itself as a conference in 1999 and currently sponsors 26 conference championships for 11 institutions. NESCAC member schools offer an average of 30 varsity sports programs. The College offers 31 varsity programs and 15 Club programs, putting it near the top of that list. The decision to offer certain sports as varsity programs versus Club programs at the College was made in collaboration with the other members of the NESCAC years ago.

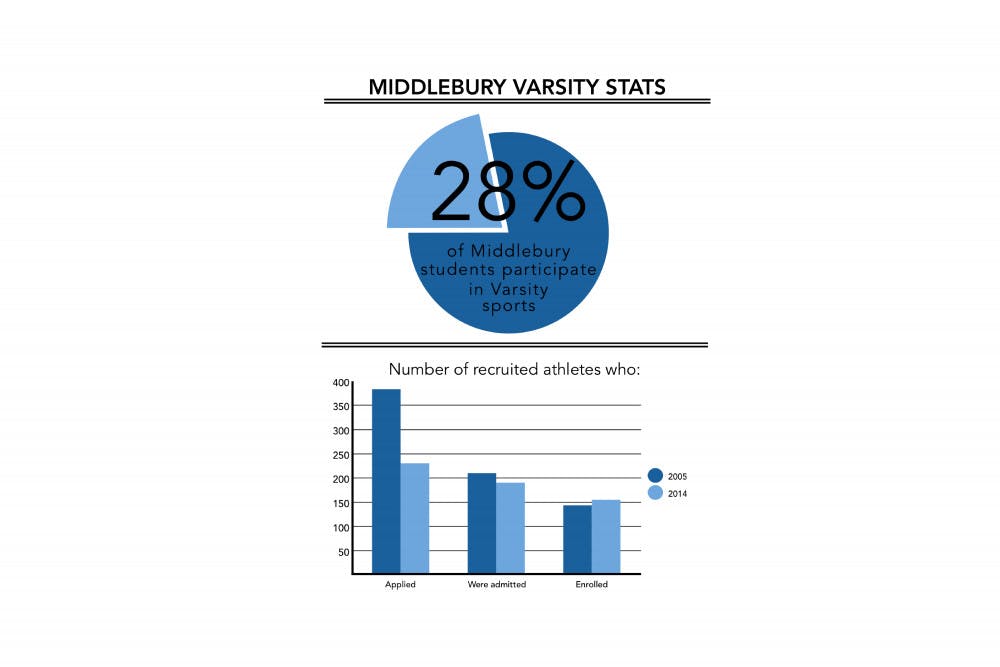

Because 28% of the student body is involved in the varsity sports program, the College has committed itself to supporting the varsity sports program on many different levels. These commitments must work in harmony with the College’s dedication to academics and a diverse and engaged student body.

Financial

Each year, the College budget reflects a number of different needs. According to the College’s budget office, “Budget decisions reflect the College’s mission and core values. Our top priorities are our academic program and our need-blind admissions policy for U.S. students.”

In the 2014 fiscal year, the College’s budget was $292 million. Of this, approximately $5 million (or 1.7%) is allocated to the athletics department on a yearly basis.

According to Athletics Director Erin Quinn, budgets are constructed to pay for the essential elements of each varsity program, including items such as food, lodging, travel and the basic equipment. This process is the same across all varsity sports at the College, including the Alpine and Nordic ski teams and the Squash teams, all of which are not traditional Division III sports but instead compete with only one division. In these sports, the College and other DIII institutions compete against DI institutions, while retaining the DIII classification and following DIII rules.

Specialized equipment is not anticipated in these budgets but can be applied for through the same process as any other department of the College.

“Some of the stuff that students might say that they paid for themselves might be the choices of those students to buy those things…Things that go beyond what a normal budget might cover, that a team arguably could do without, shouldn’t necessarily be covered by the budget,” Quinn said. He added that if the budget does not provide the entire cost of an item, teams may raise money and then families often contribute the difference; for example, spring trips are not fully funded by the budget. (see spread in Features)

Other organizations on campus are not included in the College’s budget. They rely on the comprehensive Student Activities fee, which was $407 per student for 2014. This money is pooled together and allocated to student organizations through the SGA Finance Committee.

Between last spring and this fall, approximately 140 clubs came in for both budget and new money requests, including a number of Club sports programs. Club sports rely on the Student Activities fee for all expenses except that of any coaches.

According to Katie Linder ’15, captain of the Women’s Rugby Club team and SGA Athletic Affairs Committee chair, figuring out finances is a large part of Club sports. “Staying in hotels the night before versus driving up at five in the morning is something that we would love but we make it work, it’s the only way we know how to operate. It’s a process, but we get as much money as we need… I can’t say that I wouldn’t like more money, but it’s manageable,” she said.

SGA Treasurer Ilana Gratch ’16.5 said, “It’s not that we run out of money, it’s that we have to discern which requests are going to have the widest reach and be the most beneficial to the most students because, at the end of the day, it’s coming from the Students Activities fee which we all paid for. It is a finite amount of money so we can’t fund everything.”

Because athletic facilities are open to the College and town communities, a separate section of the College budget provides for these facilities. However, the construction of the new Virtue Field House and the Squash Courts was not included in these numbers. The $46 million project was the first of its size completely funded by donors, many who have previously given to the College’s financial aid, to academic programs, or to other College initiatives outside of Athletics.

Although College fundraising efforts are not directed towards athletics, research shows that often athletics are a source of inspiration for alumni donations. In 2006, Professor of Economics Jessica Holmes published a paper using 15 years of data from the College which concluded that alumni, regardless of whether they were involved with athletics or not, tend to donate to the College when athletics are doing well or when academics are doing poorly. Although the data is not recent, these results remain relevant to the College according to David K. Smith ‘42 Professor of Applied Economics Phani Wunnava.

Tim Spears, Vice President for Academic Development and a leader in fundraising efforts at the College, said, “In the larger world of intercollegiate athletics, one of the reasons why booster clubs exist at universities and the like is because through successful athletics programs, you raise awareness for the school and build loyalty. There may be merit to this approach, but that’s not the strategy that’s at work at a place like Middlebury.”

Admissions

Under NESCAC guidelines, the College may not admit recruited athletes until they have gone through the same process as any other applicant. However, coaches can get feedback from Admissions about where to prioritize their recruiting and, according to Dean of Admissions Greg Buckles, “The boundaries of that get pushed a lot.”

Recruited athletes are often given extra and earlier advance notice as to their viability as a candidate for the College based on criteria set by the NESCAC, which can often lead athletes to premature assumptions about their admittance. Instances have occurred where students in the recruitment process have claimed a “commitment” to the College similar to those allowed at Division 1 institutions. As a matter of protocol and process, Buckles said, Admissions will track down these claims to correct them when they see them.

“[The NESCAC recruiting process] is at the same time the most confounding but also the most noble undertaking of any athletic conference I know of,” said Buckles. “In other words, it’s complicated, it can be confusing, frustrating, and sometimes it will seem like it’s hypocritical but, in the end, it works well. We keep a lid on the appropriate amount of emphasis on athletics and at the same time we’re very successful.”

Recruitment success is a significant part of assessing the performance of Coaches, and so they are part of the admissions conversation. However, the same process exists for the Arts department. Through the same evaluative system as the Athletics department, members of the Arts may convey to admissions which candidates they would like to see admitted. Furthermore, any department or any faculty member can oversee potential candidates in whom they have an interest and may open a conversation with Admissions.

In the Athletics department, the ability to evaluate applicants has proven beneficial to the overall application process. In any given year, about 25 percent of the incoming class is recruited athletes. This number has remained constant while the total number of recruited athletes who apply has been shrinking (see graphic on front page).

The recruiting process also encourages more athletes to apply Early Decision. In 2014, 44 percent of Early Decision 1 applicants who enrolled were recruited athletes. “The upside of that is that interestingly leaves room for more non-athletes because it’s typically one-for-one…That leaves us, in some sense, with more room to consider a whole host of other needs and goals for the class,” said Buckles.

The recruiting process at the College across all varsity sports is consistent with those of the ten other NESCAC institutions. This process is one of the most restrictive in the country and has caused a lack of diversity in athletics. Between these restrictions and a lack of resources to travel extensively or reach out to athletes, Coaches are often limited to those athletes who have the ability and the connection to NESCAC institutions to approach coaches themselves.

“Almost everywhere else, a lot of times athletic conferences and athletic teams will support more diversity…As we’ve made great progress and strides in the overall student body…that has not been reflected in the athletic teams as much,” Buckles said.

“A coach puts together the class holistically just the way the College does,” Quinn said. “We try to be very consistent and we try to have the athletic department be representative of the College. We have some limitations on our ability to recruit as broadly due to practical, financial considerations as well as NESCAC restrictions on recruiting. The NESCAC has looked carefully at some of these practices as well. How can we create the most diverse pool as possible? Are there league restrictions that prohibit us from doing so?”

One way a lack of diversity in athletics might be addressed is by looking at athlete GPAs or how financial aid is allocated to athletes and non-athletes on campus. According to Quinn, athlete GPAs are tracked internally by the Athletics Department periodically to evaluate the academic success of student-athletes, but these numbers are not open to the public, just as GPA numbers are not available for any other campus constituencies.

Additionally, because of the College’s need-blind policy, financial aid numbers for specific groups are not tracked except through annual audits on the Student Financial Aid office, of which the results are not shared unless an issue becomes apparent.

Time Commitment

Students’ commitment to athletics is often seen as a diversion from the College’s commitment to academics. Although the College outlines specific procedures for students, coaches, and professors, it is often left to the discretion of those involved how to balance athletics and academics.

“One of the things that we think about a lot as faculty is student time and whether or not students have the time that they need to devote to their academics,” said Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculty Andi Lloyd. “What’s the right amount of time to devote to academics relative to extracurricular activities? It’s a question about time as a scarce resource.”

Lloyd also commented on claims that student-athletes are given access to easier classes. Although unaware of any specific practices concerning this she said, “The kinds of things I hear—and the kinds of conversations I have with my advisees—have more to do with time management than with taking easier classes… I think people are making choices about classes based on any number of different factors, including athletics and other extra-curricular commitments. I would not define it as an issue of athletic privilege in the sense that it is playing out at other schools.”

By College and NESCAC regulations, varsity athletes are limited in the amount of time they are allowed to practice, how long their season is, and how many games they may compete in, among other things. However, the time commitment to a varsity sport is still substantial and, for many students, a deciding factor for participation.

“I came in and I picked rugby because I wanted to learn the sport but also because I didn’t want to try to play a varsity sport,” Linder said.

She added, “We have a lot of girls who played sports in high school and didn’t want the commitment of a varsity sport because it’s a huge time commitment and we’re sort of looking for a middle ground where it was a structure, a team, but wasn’t that much of a high competitiveness level.”

Lloyd added that this conversation extends beyond athletics. “Having been here for almost 20 years, I have seen that students find any number of different pathways through this place, they distinguish themselves in any number of different ways, they find a range of things outside of the classroom in order to stretch themselves and challenge themselves, and athletics is one of those things but, it’s not the only thing,” she said.

Social Life

The divide between athletes and non-athletes on campus goes beyond areas in the budget, admissions and time commitments. The op-ed published in The Campus, a response by basketball player Jake Nidenberg ’16, and another published on Middbeat by Lizzy Weiss ’17 and Aleck Silva-Pinto ’16 are all part of the ongoing conversation around this divide.

Many have pointed to freshman orientation as the origin of this separation between athletes and non-athletes. In the 2015 SGA student life survey, participants were asked if they think the staggered arrival of fall athletes, international and non-athlete domestic students during orientation impacts relationships between different groups. Results showed that 16.13 percent of participants saw a positive impact, 59.04 percent saw a negative impact, and 24.83 percent saw no impact.

In their column “NARPs” in the Campus, Maddie Webb ’17 and Izzy Fleming ’17 have explored how non-athletes at the College can get involved with both athletics and other activities on campus. “‘NARPs’ is a term I had never heard before I came to Middlebury,” Webb said. “Most people use it as a term of endearment but there are also people who use it to put other people down.”

She added, “There are so many people on this campus who think that sports are everything and you are nothing without athletic ability and so a point of our column is to not only take back the term NARPs but to show people all the opportunities there are on campus to get involved that they might not have known about.”

As head of the SGA Athletic Committee, Linder works to bridge this gap. “A lot of what we do is how to get more people to come to games and support the team and school spirit…I think we run into issues less with privilege and more with the disconnect between athletes and non-athletes and trying to find ways to make a connection between those two sides,” she said.

Whether athletics are seen as an outlet for extra privileges or a source of diversity and connection on campus can be attributed to how students at the College embrace the divide. “This is college, and we love to refer to Middlebury as a bubble, and that’s not a bad thing—to an extent, it should be a bubble,” Spears said. “This place, of all places, of all moments in students’ lives, should be where people are crossing those boundaries and getting to know people who are different from one another.”