This has been a good year for movies. Tom Hanks gave a mesmerizing performance in Captain Phillips, Mud captured the spirit of the South with subtle grace, and 12 Years a Slave depicted slavery without resorting to revisionist comedy and violence. The movie that most blew me away, however, was Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street. Unsurprisingly, as Wolf has garnered as much criticism as acclaim, ambivalence towards its 180 minutes of relentless and unabashed sex, drugs, and pump & dump isn’t really an option.

The Wolf of Wall Street tells the story of Jordan Belfort, a former stockbroker whose career was cut short by dozens of felony convictions on charges of securities fraud and money laundering. Indeed, he cut himself short. This wasn’t hubris; it was intentional criminality. As one of Belfort’s prosecutors and Middlebury graduate Joel Cohen ’84 says, “[Belfort was] a guy who woke up every day [...] and said, ‘What crimes can I commit today?’

Scorsese does not shy away from bringing these crimes to life. In almost every scene, we see Belfort or one of his cronies break the law. They are constantly under the influence of drugs (cocaine and Quaaludes are usual suspects), they inaugurate a new elevator in their building with a statutory rape, and, of course, they establish Statton Oakmont with the sole purpose of scheming and stealing from investors. Yet, for every crime, there is a victim, and critics of the film insist that many of these victims are not given the focus or face-time they deserve. I’d agree if this was a movie about condemning Belfort, but it’s not. Wolf is about a lot more than that.

The film opens with Belfort snorting blow out of a hooker’s ass before abruptly cutting to him receiving conjugal road head while speeding down the Long Island Expressway. If you saw the movie and weren’t at least a little titillated after the first sixty seconds then my hat’s off to you. From there, the movie barely slows down, orgies and drug binges become commonplace, but so does Belfort’s selfishness. He is portrayed — quite rightly — as a compulsive liar and a cheat, to both his clients and his wife, Nadine. In one of the darkest scenes of the movie, Belfort hits Nadine before driving drunk and high with his young daughter in the passenger seat. There should be no doubt in anyone’s mind as to the moral depravity of the title character and yet he just seems so likable and inviting. Perhaps its a testament to DiCaprio’s performance, but you can’t help but want to spend a day with Belfort.

Wolf is less of an exposé of Belfort’s crimes than a mirror of the American psyche. Last week nearly eight million people watched ABC’s The Bachelor, now in its eighteenth season. That’s right, millions of people actually tuned in to watch a glorified and one-sided mating ritual. A year after twenty children and six adults were murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary School thirty-two million people had purchased “Grand Theft Auto V” and not a single law had been passed by Congress to restrain gun violence. Justin Bieber’s marijuana use is headline news and Robin Thicke can make a song about rape into a platinum record by putting naked women in the music video. The only thing more exciting to the American people than a movie about drugs and violence is a movie about drugs and violence starring a woman in black leather. We tell ourselves that these are guilty pleasures, but such assertions are nothing more than evangelical pretension.

With Wolf Scorsese tests this lust for perversion: when the veil of fiction is removed will we still fall for the villain? Needless to say we failed the test quite miserably. People criticize the director for glorifying Belfort, but not the viewer for eating it all up. Art is made so that those who encounter it question the very fabric of the world around them. A simple recitation of Belfort’s transgressions is better fit for the front page of the Wall Street Journal than the silver screen. In Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a middle-aged man, lusts after a 14-year-old girl, eventually raping her. My (much missed) co-columnist, Harry Zieve Cohen, tells me that the brilliance of the book lies in how difficult Nabokov makes it to resist feeling at least some excitement in reading about the protagonist’s wicked behavior. This analysis also holds for The Wolf of Wall Street. The very elements of the film that many denounce are exactly what makes it so great. Indeed, the very fact that people see the film as a glorification of Belfort is evidence that they, like I, were unable to fully resist the attraction of vice. In portraying Belfort as a hero, Scorsese makes us the villain. Could we really say he’s wrong? In portraying Belfort as a hero, Scorsese makes us the villain. Maybe he’s on to something...

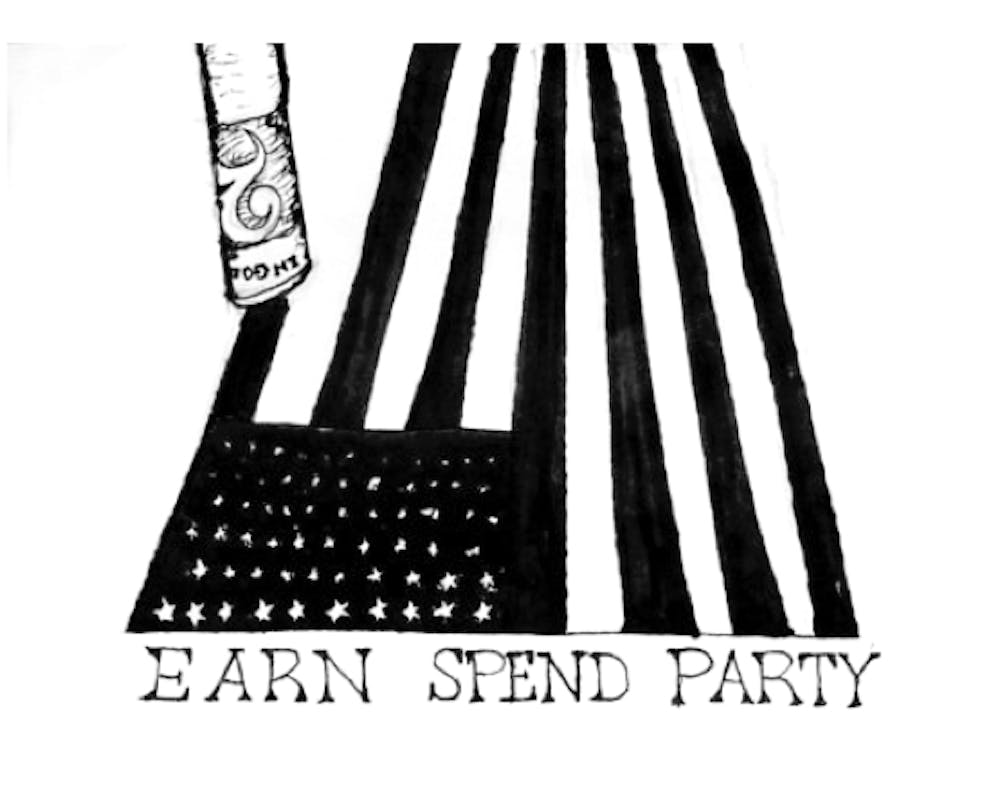

Artwork by SAMANTHA WOOD