“Organic isn’t some high-in-the-sky idea; green isn’t some exotic goal,” said Larry Plesent, CEO of Vermont Soap Organics. “It’s just what you do.”

For the past 18 years, Vermont Soap Organics has manufactured organic, all-natural cleaning products and soaps. At the company’s Outlet Store and Factory, located on Exchange Street in Middlebury, customers can buy reduced-price products. Inside the store, bathtubs of organic bar soap, bottles of natural yoga mat cleanser and foamy hand soap surround visitors.

Plesent led me on a factory tour where organic raw materials are processed into foamy products. He pointed out Vermont Soap’s most recent achievement which was being packaged during my visit: FungaSoap. In collaboration with a podiatrist, Plesent and his team have spent the past seven years creating a soap that fights fungal infections. The popular manufacturer PediFix has picked up the product and will distribute it to stores all over the world.

Plesent’s decision to enter the soap-making business was prompted by his days working as a window washer. He noticed that cleaning solutions gave him rashes, which persisted even after testing a slew of soaps. Frustrated with the products on the market, Plesent became committed to creating an all-natural, irritant-free soap.

His search for the ideal base for cleaning products resulted in Liquid Sunshine, a combination of saponified organic coconut, olive and jojoba oils, essential oils, organic aloe vera and rosemary extract. Liquid Sunshine revolutionized all-natural cleaning solutions and created the world’s first all-natural shower gel.

Most cleaning products are primarily composed of Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS), a chemical compound classified as a primary skin irritant, but the base for Vermont Soap Organics’ varieties of bar soap is composed of coconut, palm, olive and palm kernel oils. The 200-year-old process to make a bar of organic soap takes approximately a month. Concentrated, natural essential oils are added to give products scents like “citrus sunrise” and “lavender swirl.”

A biology and chemistry student, Plesent takes a scientific approach to his company’s “green” practices. He sees a correlation between the introduction of synthetic molecules from factories in the past century and increases in health and environmental problems. According to Plesent, the clothes you wear, the shampoo you use and the air you breathe are composed of synthetic molecules, which are possible carcinogens.

“If you want to be green, you’re going to have to think about molecules,” he said.

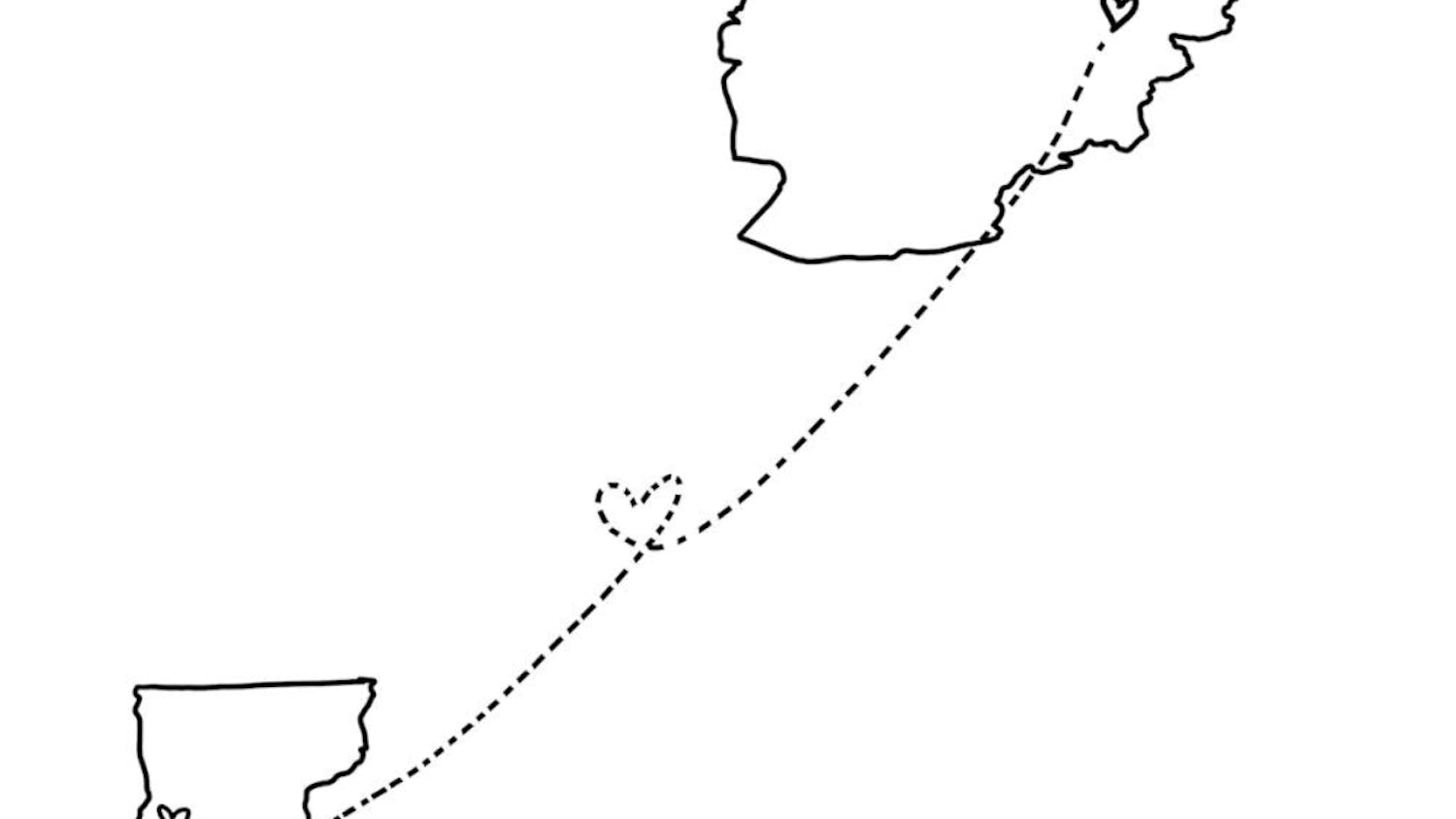

Vermont Soap Organics is also linked to the global economy. Natural materials are imported from Colombia, Brazil, the Philippines and West Africa.

Plesent established economic and personal connections in West Africa when he traveled to Ghana and Guinea. A non-governmental agency looking for experienced soap makers to teach the trade to an African village approached Plesent. He became interested in traditional methods of shea butter production and traveled to Guinea to observe and document the process in which oils are extracted from shea nuts. Shea butter aids burns, skin irritations and wrinkles.

In addition to the company’s retail outlet and website, Vermont Soaps distributes products to independent retail stores and Whole Foods in New England. Although Wal-Mart wanted to use his company to build the chain’s organic household product line, Plesent refused because they would have had to outsource production.

“Green is a process, not a result,” said Plesent.

Local Wanders

Comments