Author: Yvonne Chen

"In our youth we all chirp rapturously like sparrows on a dung heap, but when we are forty, we are already old and begin to think about death. Fine heroes we are!" remarked Anton Chekhov in reference to the lack of positive heroes in his writing.

Professor of Theater Douglas Sprigg chose to direct a production of "The Three Sisters" this spring because he was attracted to Chekhov's distinct treatment of comedy, tragedy and pathos.

Chekov's dense dialogue and complicated subtext created extra obstacles to an easy understanding of his plays. The dialogue and atmosphere of "The Three Sisters" is very naturalistic, but this sometimes proved confusing as characters interrupted each other, often having lines that came from their own internal monologue rather than from interaction with other characters on the stage.

The play opened with sisters Olga (Lindsay Haynes '02), Masha (Megan West '02) and Irina (Kristin Conolly '02) on stage together. These three sisters and their brother Andrey (Freeman White '03) were struggling to subsist on the minimal military pensions that they received after their father's death a year earlier. Spinster Olga worked as a schoolteacher, unable to find fulfillment in her job. Young and radiant Irina dreamed of love and of returning to the excitement of Moscow.

The scene was Irina's birthday and soldiers came, bearing gifts and wishes. We were introduced to Baron Tuzenbach, played by Nick Olson '02, who has been in love with Irina for five years. Vershinin, played by Jesse Hooker '02, the colonel of the regiment, introduced to the conversation a contemplation of the future and dreams of a utopian progression towards happiness.

As the play moved into the second act, hope for this ideal future ebbs away and the character's lives fall apart before our eyes. The darkness of winter is lighted only by the dim candlelight of the new head of this household, Natasha (Tara Giordano '02) whose domineering presence and selfish complaints bring unease to everybody. The three sisters complain of the degenerative influence Natasha has over her husband, their brother Andrey.

The sisters themselves are not free from temptation however. Vershinin's philosophizing, for which he always apologizes, entices the bored Masha, who married her professor at 18 for his intelligence only to discover that he was not as intelligent as he seemed.

One got the feeling that none of these characters would be happy living their hoped-for lives. Just as soon as each character's passions rose they appeared to be quickly thrown aside by another character's interruption. For instance, as Vershinin contemplates the nonsense of life, almost out of nowhere Masha's husband Kulygin (Tim Brownell '02) comically jumps in with an anecdotal story about how one student mistook the word nonsense for consensus. In a later scene, just as the commander delivers one of the more definitive lines of the play, "As time passes you will realize you never get the beautiful life you dreamed of," guests rush quickly in to wish him goodbye.

Sprigg explained that Chekov developed a technique that shows "little things about characters that come up and then disappear." In this production, Sprigg sought to communicate the subtlety of how the written word functions. With his expert perspective in mind, one might say that this production of "The Three Sisters" is an intellectual representation that forces the viewer to pay attention to the subtleties of what everyday life is all about, rather than a production that sought simply to enteratin. Other experts such as Russian professors Michael Katz and Tatiana Smorodoinska spoke very positively of the production.

Kulygin and Solyony's high mannered performances do an especially good job of interjecting comedy, whereas the more likeable characters such as Olson's lovesick Baron, West's animated Masha and Hooker's philosophizing Vershinin, help to provide gravity. However, at times, such as when Kulygin is calling out to Masha or when he forgives her in the end, the audience seemed to respond to these actions with too much laughter.

"There's no question that some people don't like Chekhov," Sprigg commented. "It has a poetic theatrical language. It takes work to pay attention to all of these things."

To a generation that has grown up with action-packed box office hits, Chekhov's distinct theatrical style may at first seem unappealing as it avoids the sensationalism of implied occurrences such as the duel.

Getting the full benefits of this major production requires specific knowledge of the narrative and the theatrical style. Assistant to the Director Sheila Seles '05 adds, "It's so complex that you can't just see it once."

In the closing act the characters are forced to become resigned to their fates. A duel takes place in which Solyony kills the Baron, who was the one person who actually understood and defended him, and, in one of the richest performances of the show, Masha grieves to say farewell to Vershinin as her cuckolded husband looks on. Moscow, as Irina beats into our heads again and again, is an ideal that remains beyond reach.

It is not until the ending speech, which is juxtaposed against the upbeat band playing for the departing soldiers, that the sisters revitalize a notion of hope. However this counterpoint too seemed spurious and forced.

In the end, one might also hope that any period production aims to present the timelessness of a predicament and thus attempts to go beyond the period in which it seeks to represent.

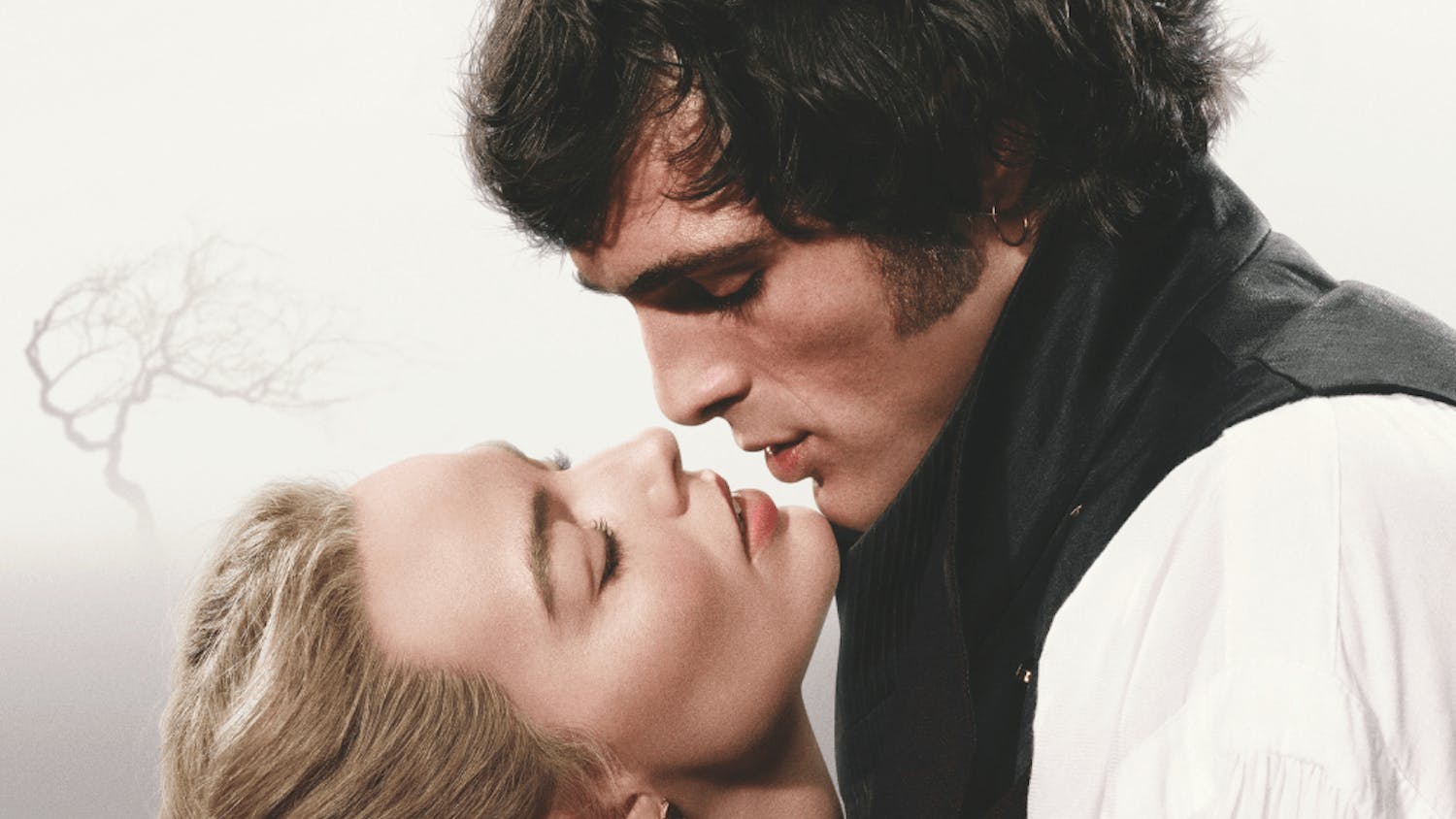

The mise en scene was as good as it gets. Artist-in-Residence Jule Emerson and Costume Shop Supervisor Lin Waters succeeded in providing the cast with a line of authentic turn of the century fashions, befitting each character's occupation.

Associate Professor of Theater Mark Evancho's light design at times foreshadowed despair with the shadows of bare trees, and other times left disclosure with the eerie fades of a tableau.

Beyond the period, however, this play speaks to the universality of the human condition. Through its themes of longing and unhappiness along with the everyday comedies that underscore the presence of huge tragedies, this play showed humans as they were in the past dreaming of today, and ultimately demonstrated what is the "stuff that makes us who we are."

'The Three Sisters' Explore the Comedy and Tragedy of Life

Comments