Author: Kate Prouty

Did you hear what Emily Wasserman '02 did last weekend?

She might not have made the history books, but she did pull off two performances of an original, 45-minute one-woman show. "Green Neon," although at times emotionally unconvincing, was nonetheless an engaging exploration of the ways in which a "girl" (played by Wasserman) understands herself as an individual versus how she is defined and suffocated by an unhealthy relationship. The girl, struggling for clarity in her own life, ironically works as a "Love Doctor" who answers the questions of helpless women in relationships.

The performance was a streaming current of monologue divided into little scenes that jumped back and forth between events in the girl's life. The collage of scenes, ranging in length from a short telephone conversation to a longer description of a first date, provided windows into the developing relationship between this nameless girl and a similarly anonymous man (ambiguously referred to as "he") whom she met at a bookstore. The windows of information, cracked barely open at the beginning, gaped progressively wider as the story unraveled, revealing more and more details to represent the girl's increasing comprehension of her situation.

Wasserman established coherence between the pockets of information by systematically inserting revised versions of how the girl and "he" first met at the bookstore. Unlike returning to the security of the unchanging chorus of a love song, "the bookstore sections" dilated as the plot thickened, each time divulging more elements about this encounter.

Wasserman delivered the first version of the bookstore section with a flirtatious smile and excited eyes. And yet, even at the conception of their relationship her happiness was tainted with overtones of foreboding complications. Was she pleased or pained that "he's getting into [her] brain, [her] blood, breaking [her] down…making [her] pay attention"? Emphasizing the word "pay," the girl implied that although she is happy about the relationship, it is also in some way oppressive.

As the bookstore scenes recurred, the girl's tone and posture become increasingly negative. By the end, her speech was abruptly punctuated, her shoulders were hunched and she stared fixedly ahead rather than wandering around the stage looking happily out at the audience as she did in the opening scene. The distinctions between the first and final retellings of the bookstore scene were clear, but the subtle nuances between each rehashing were not always fully developed. Wasserman's intonation and movement choices did not clearly reveal how she identified with her relationship.

This ambiguity was not necessarily a bad thing. In her defense, Wasserman explained that the girl's movement and vocal intentions were sometimes vague "because until the final bookstore scene the character is really incapable of fully understanding what has happened, and she ends up lying to herself each time."

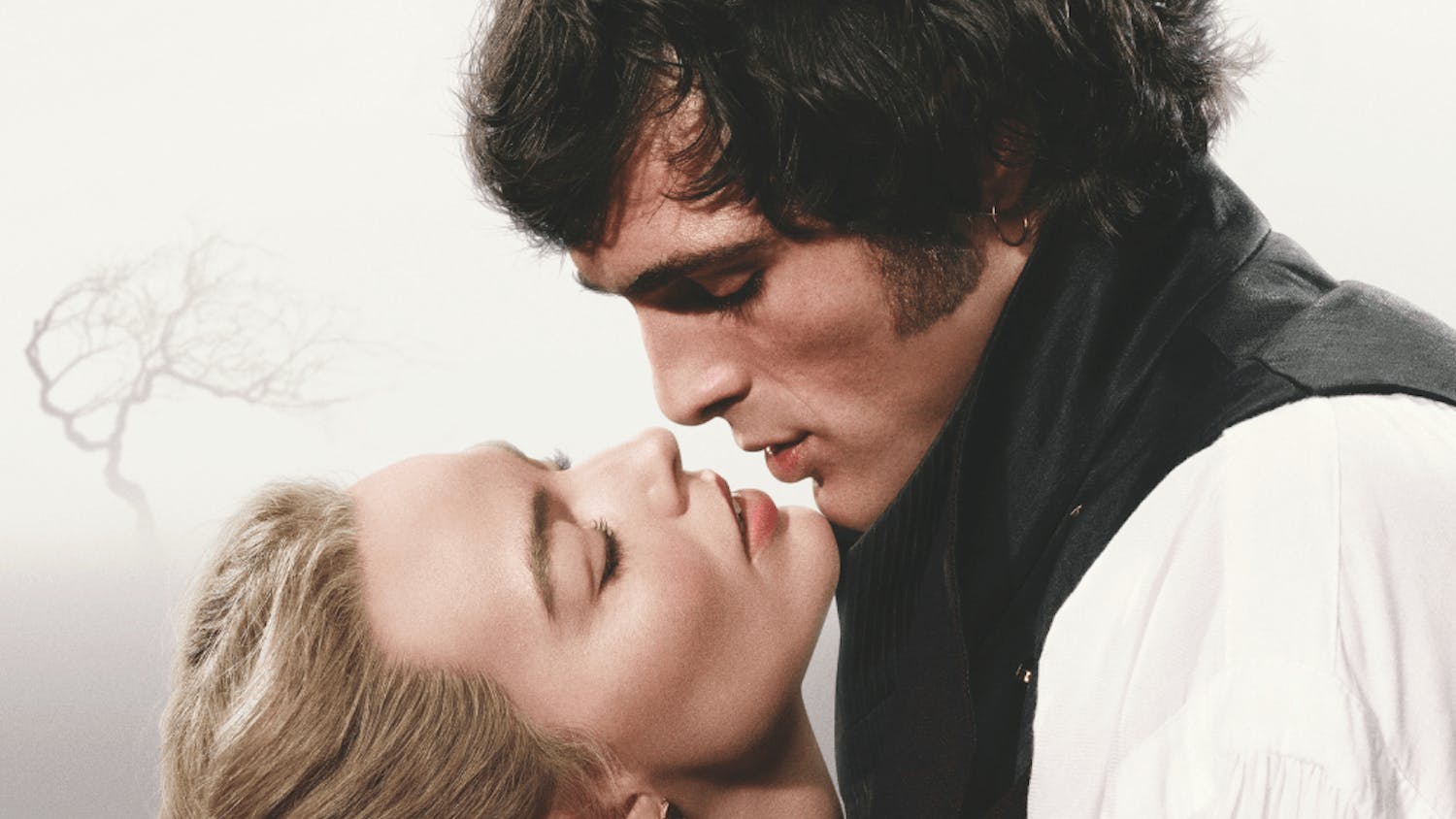

Although the performance choices were shaky and thus at times emotionally unconvincing, the script was polished, allowing important details about the recurring scene to trickle in subtly yet noticeably. The present he bought for the girl is narrowed down from a nondescript book to something written by Emily Brontë and is finally specified as "Wuthering Heights." Because it is "foreboding," Wasserman felt that "Wuthering Heights" was "the perfect book to reflect the type of relationship that this character finds herself in."

When considered in retrospect, "Wuthering Heights" actually has very much, thematically and stylistically, to do with "Green Neon." They both investigate the destructiveness of overly dependent love. Catherine and Heathcliffe's (the protagonists of "Wuthering Heights") love is based on the shared perception that they are identical. Catherine famously declared "I am Heathcliffe" and Heathcliffe, upon Catherine's death, wailed that he cannot live without his "soul," referring of course to Catherine.

In "Green Neon," too, there was an insistence upon the bodily invasion inflicted by an unhealthy relationship. In the more abstract sections of the girl's monologue, she wondered if the bones beneath her skin are hers or if she is just a shadow of her lover. She felt "he has swallowed [her]" because he has taken away her freedom to determine her own identity.

Although the reference to "Wuthering Heights" made for an interesting dialogue with "Green Neon," it is not revealed for the audience until the end. Hiding the title of the book created suspense but it also limited the possibility of strengthening "Green Neon's" plot by allowing the audience to make the literary connection.

By the last bookstore section, the girl finally came to the conclusion that "[she doesn't] want this." Although the antecedent of "this" is of course the book, the realization represents her final understanding of the destructiveness of her relationship. She does not want him.

Despite the burdensome relationship that drove its plot, "Green Neon," like "Wuthering Heights," ended with rebirth. Just as Heathcliffe and Catherine's relationship is replaced by Hareton and young Catherine, the girl in "Green Neon" triumphantly declared that by regaining her independence she will, like a lizard, "grow [herself] back."

Overall, Wasserman's script was her biggest success. While her written themes were clearly delineated, their delivery was sometimes obscured by uncertain performance choices. As Wasserman explained, "[Green Neon] was really an impromptu project that grew into a wonderful process and experience."

One-Woman Show Glows 'Green Neon'

Comments