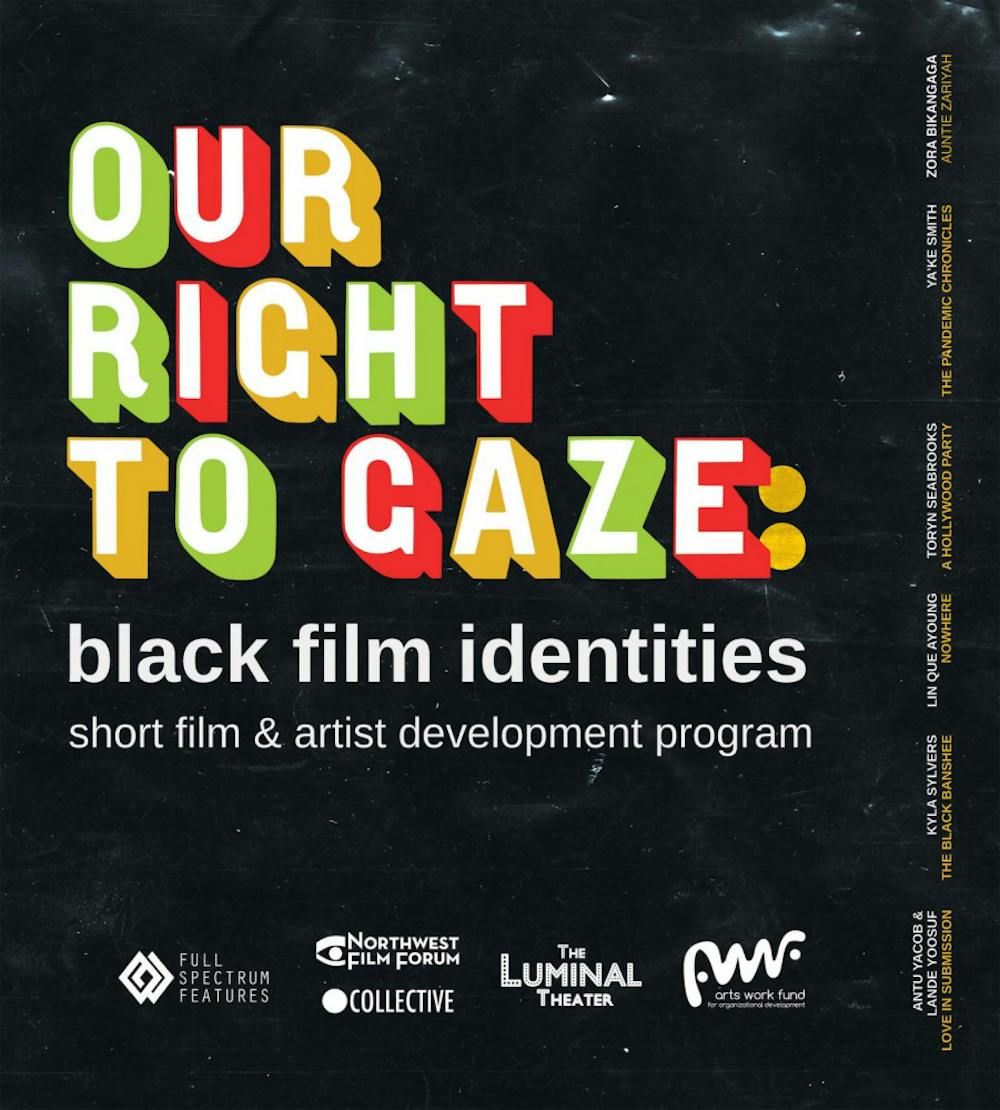

The Hirschfield Series kicked off this spring with “Our Right to Gaze: Black Film Identities,” a collection of short films by Black filmmakers. The collection is a collaboration between Full Spectrum Features, Northwest Film Forum, The Luminal Theatre and Circle Collective. A few of the series’ creators, namely Antu Yakob, Zora Bikangaga and Curtis Caesar John, joined the Middlebury community for a post-screening Q&A on Saturday night over Zoom.

“Love in Submission,” directed by Lande Yoosuf and produced by Antu Yakob, was the first of the six short films. It explores a dramatic conversation between two Muslim women shocked by newfound secrets about their connection. The film captures a side of the Black Muslim experience that we don’t often get to see on screen, presenting characters living different lives under the same identity umbrella. Originally an on-stage production, “Love in Submission” underwent serious development to become a short film. Yakob and Yoosuf are currently working on expanding the story once more, this time into a full-length feature.

Following the melodrama of Yakob and Yoosuf, “A Hollywood Party,” directed by Toryn Seabrooks, lends quick comic relief to the series. A young waitress meets her celebrity hero, only to find that he has spit crumbs onto her lip mid-conversation. Seabrooks, starry-eyed and eager to please in her role as waiter, all but falls apart in a hilarious, quivering performance. The scene cuts between her and her famous companion, who prattles on obliviously about the inspiration of Maya Angelou.

The third short in the series, “Nowhere,” directed by Lin Que Ayoung, follows a disheveled and traumatized wife freshly wounded after an episode of domestic violence. She strays into a BDSM club, encountering a world where, to her surprise, control is a choice. Thinking of her violent marriage, she asks a submissive member of the club, “Why would you ever want to be controlled by someone?” in confusion, to which he refutes her judgment by revealing his deliberate preferences. From fear and hesitance, actress Edna Lee Figueroa projects a liberating metamorphosis onto the character of Esther, rewriting her restrictive outlook on sexual diversity and freedom as a couple in the club shows her the ropes.

“The Black Banshee,” directed by John D. Hay Jr. and produced by Kyla Sylvers, follows a group of four partygoers on a night out. Merrymaking is cut short as a friend is overtaken by a vision of police brutality. She foretells a tense standoff between her friends and a few suspicious cops; the conflict escalates to the point of imminent, graphic death. Unfortunately, this is a familiar story, told time and again while the fight for Black lives persists. “The Black Banshee” pays homage to the hardened realities of living while Black in the U.S.; its title acknowledges the impact of spiritual consciousness, sometimes present in the most foreboding of ways.

Next up, “Auntie Zariyah,” directed by Zora Bikangaga, follows a stand-up comedian, played by Bikangaga himself, making his way down to Seattle for a show. He lodges with the eponymous Auntie Zariyah, who is later revealed to be a 12-year-old influencer. The film is topical and fun, and throws a zesty spin on how Bikangaga describes the quintessential “auntie.” Bikangaga credits actress Zariyah Quiroz’s charisma and talent as inspiration. “I didn’t cast it for anyone — I wrote it for her. [...] It became a kind of dedication to the aunties that were important in my life. Aunties are a big part of Ugandan culture, East African culture [and] Black diaspora culture,” Bikangaga said. Lastly, for those wondering: yes, he is technically her nephew. Bikangaga’s on-screen father drawls, “Well, your granddaddy was a rollin’ stone. Rolled all the way to his grave.”

“The Pandemic Chronicles” finishes the lineup. Director Ya’Ke stitches together three perspectives of the past year: the comedic, the desperate and the longing. First, we see a young couple on a date, six feet apart until they close the gap, pressed together without nitrile gloves or 3M masks. Second, we see a tragedy onset by medical insecurity, as the film investigates the discriminant effects of healthcare during this tense time. Third, a family is torn apart in the face of danger, when a husband and wife struggle to connect with a wall separating them.

Overall, “Our Right to Gaze” wholly dedicates itself to showcasing the range of Black identity in art. It provides a necessary space for underrepresented creators, opening doors to diverse work. As Yakob noted, “Blackness does not equal one identity.” “Our Right to Gaze” is an anthology everyone can experience soon, as the series will be made available in the coming months for widespread release.

Reel Critic: ‘Our Right to Gaze’

Courtesy Photo

Comments