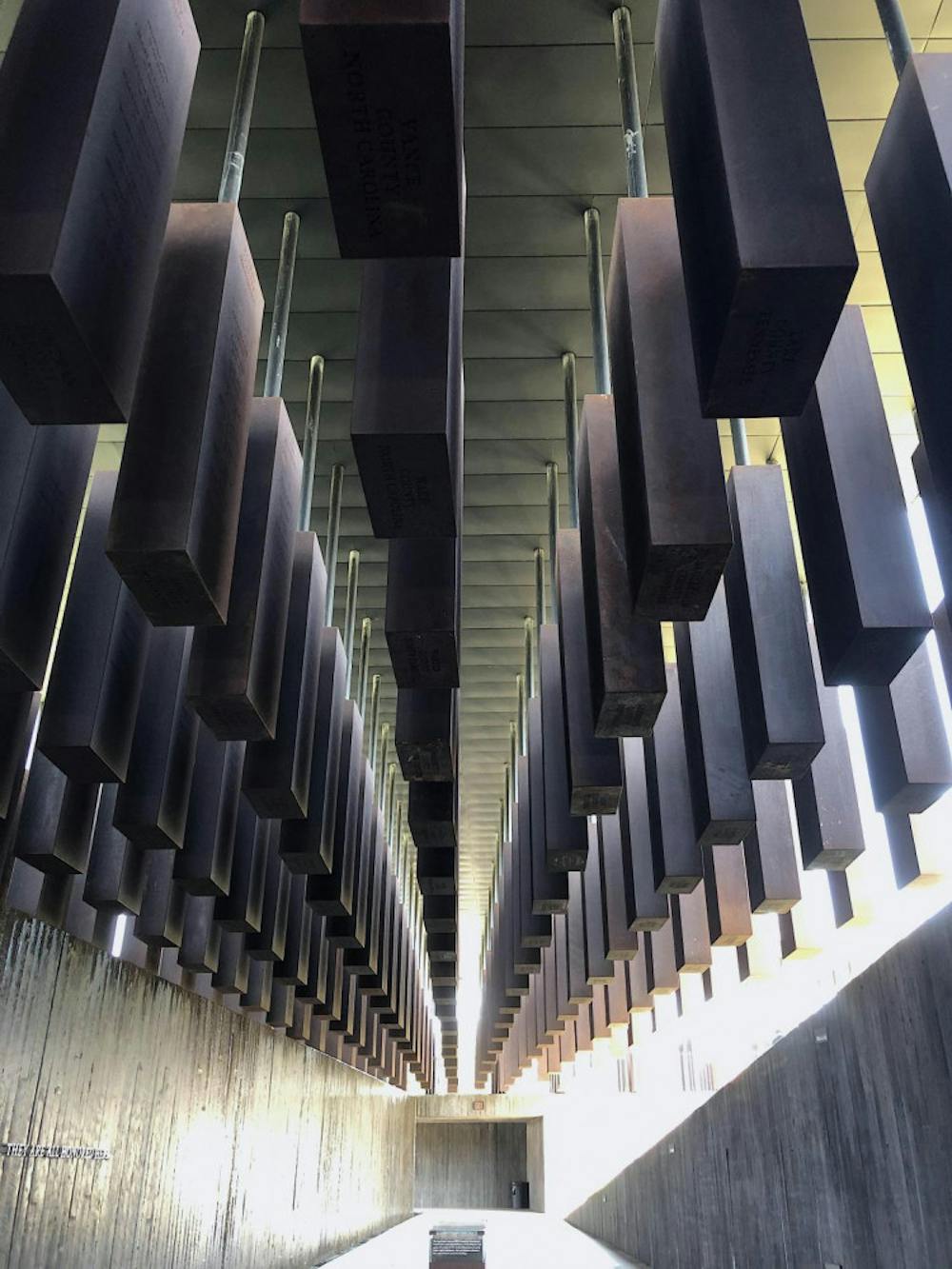

I recently traveled back to my parents’ home in Alabama. While there, I visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the country’s first memorial dedicated to Black victims of slavery and lynching. The memorial is an emotionally powerful and visually stunning history lesson. It is a small but welcome step in Americans owning up to the legacy of our forebears.

The monument was well-designed. For every county in America in which there was a documented lynching, there is a suspended steel column that echoes lynching’s grisly, grotesque inhumanity. There are over 800 columns. There is a jar of dirt from every lynching site in Alabama. They needed a whole wall for the jars. The monument conveys the magnitude of the crimes (4,400 people killed and millions intimidated) without losing sight that each victim was a person with a story. It’s haunting and gut-wrenching. As it should be.

The point of a monument is twofold: 1) it is society choosing what historical events to highlight and 2) it is society sending a message to itself about what it wants to be today. Monuments to Confederates have been a contentious issue lately. Most of them were erected in the early 20th century as an effort to remind African-Americans of who still held the whip hand in society, literally and metaphorically. There have been many, including myself, who have advocated for the removal of those monuments.

When we’ve done so, we’ve been accused of wanting to erase history. We’re not trying to erase history. We’re trying to erase pride in the Confederacy. If a person wants to take pride in Southern cuisine or football or something else not tied to racism, they should feel free to do that. But the Confederacy and the racial apartheid that came in its wake were built, top-to-bottom, on white supremacy and enforcing racial hierarchy with lynching-centered terrorism.

The point isn’t to tell people to not to think about history. The point is to tell them that whatever else their great-great grandfather who fought for the South might have done, the very act of fighting for the South was so reprehensible that no one should have any positive feelings about him. He was, like the larger Confederacy, morally irredeemable. There are no clearer bad guys in American history than those who committed treason for the purposes of committing atrocities, the traitors who fought to defend slavery and oppression.

Understanding history is not a problem; lionizing Confederates and the Jim Crow South is. We can have history, but that history needs to be in monuments like this one that help us own up to, and perhaps one day atone for, that past.

Monuments are also about the present. The present-day point of this monument, and hopefully more like it, particularly when combined with taking down Confederate statues, is to send a message to two groups. Hopefully, it conveys to racially resentful white people that their grip on society is little-by-little weakening. The historical narratives they’d like to convey won’t go unquestioned; the historical narratives they’d like to conveniently forget will be highlighted.

Hopefully, it also sends a message to Black Americans that the injustices perpetrated against their predecessors are finally being acknowledged, even if only in this tiny way for now. Black Americans deserve to have their history heard too. The real erasure of history is not the tearing down of Confederate monuments but rather the broader refusal to come to terms with what slavery meant because white Americans would rather not talk about that. The brutal history of slavery, of the convict labor and sharecropping systems that were slavery by another name, of Jim Crow, and of mass incarceration —those are the histories that people have tried to erase. This monument epitomizes the refusal to erase that history. If American history truly is something you cherish, you ought to have some profound feelings about this monument and what it represents.

We as a nation did wrong by our Black citizens. We can do better. We must do better. That starts by saying “We understand what we did and we’re sorry. No buts. We did wrong and we’re sorry.”

Reconciliation starts with forgiveness. Forgiveness can’t happen until there’s a genuine apology. That apology can’t happen until there’s a genuine appreciation of the real history, not the airbrushed one constructed to avoid making white people squeamish. This monument is a first step on that path. Hopefully, two centuries of slavery, another century of terror and apartheid, and fifty years of indifference and inequality may finally yield to an era defined by the concepts embodied in this monument’s name: peace and justice.

Gary Winslett is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department and the International Politics and Economics Program.

In search of peace and justice

Gary Winslett

Gary Winslett

Comments