NEW YORK (SI) — If anyone deserves his spot on the Wheaties box, it’s the Olympic champion Michael Phelps. He’s the most decorated Olympian ever, having set world records in four consecutive Games. Though his specialty is the butterfly, he took to the front crawl for his race with a great white shark, which was televised July 24 on the Discovery Channel.

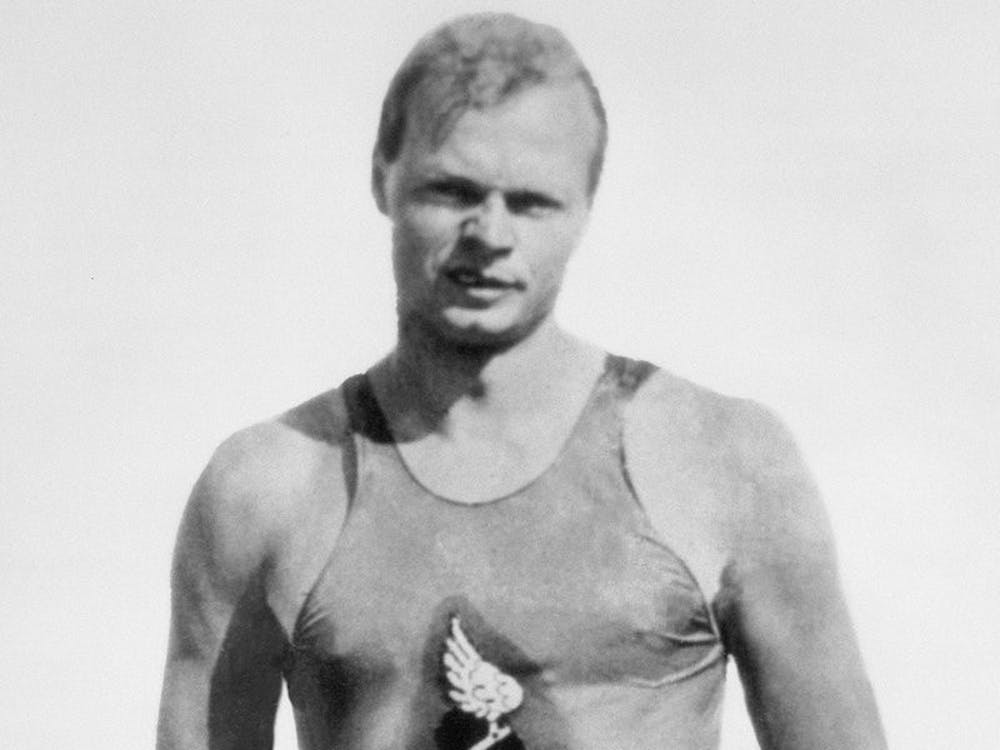

But the ubiquitous stroke known as freestyle wasn’t used professionally until another American champion perfected it: Charles Meldrum Daniels of New York, born 100 years and three months before the Baltimore Bullet. Daniels developed the stroke from the old-school “trudgen,” an unwieldy combination of a one-sided overhead stroke and a scissor kick. He replaced it with a six-beat flutter kick and a continuous stroke pattern.

English gentlemen, who had dominated the sport since the 1800s, considered the front crawl to be barbaric and “un-European,” and continued to swim only the breaststroke in competition. That is, until Daniels started beating everyone in the pool. He went abroad to England in 1905, a year after his Olympic debut in St. Louis, to swim against the best British swimmers in their home waters. He came home undefeated.

“In five years Daniels has lifted American swimming from the rut in which it lay and placed it on par with other nations,” wrote Daniels’s trainer in the Pittsburgh Press after he won the 100-meter freestyle in the 1908 London Games. But Daniels did more than put the U.S. on par—he made it a powerhouse. He is the reason why swimmers now use the American crawl during freestyle events.

Daniels was born in 1885 in Dayton, Ohio, and moved to New York City as a young child. He learned how to swim at age 12. He joined the New York Athletic Club and was introduced to competitive swimming. At 19, Daniels became the first American to win an Olympic medal in swimming, which he did in St. Louis on Sept. 5, 1904. It was a silver medal in the men’s 100-yard freestyle, held in a man-made lake in the heart of the city.

Over his career, he won eight Olympic medals: three golds, a silver and a bronze in St. Louis, a gold in Athens in 1906, and a gold and a bronze in London in 1908. This eight-medal total was an Olympic record that stood until the 1972 Games in Munich, when American swimmer Mark Spitz broke it. Spitz also won seven gold medals in that Olympics, another record that stood until Phelps won eight in the 2008 Beijing Games.

At one point in 1911, Daniels held world freestyle records at every distance from 25 yards to one mile. He posted 14 world records within a period of four days in 1905.

“I am going to stop racing after this spring,” he told the San Francisco Call in 1911, reflecting on his career. “Understand, after I retire—if there are life preservers enough to go around, I shall simply crawl into one and float until some kind-hearted soul picks me up. No, siree; I won’t even swim ashore.”

Daniels became a squash and bridge champion at the New York Athletic Club. The year after his retirement, he purchased 5,000 acres of land in the Adirondacks, New York, with his wife, Florence Goodyear, an heiress to a vast timber fortune. Daniels built a 9-hole golf course on his estate called Sabattis Park. The course entertained some noted players, who spent their summers on the property.

(Phelps is also an amateur golfer. He holed a 159-foot putt at the Dunhill Links in 2012 in what is thought to be the longest televised putt ever.)

Despite his pledge not to race again, Daniels continued to swim on the lake beside his golf course. He was an early riser and made a ritual out of his morning workouts. He would swim two miles across Bear Pond and have a servant meet him with hot coffee and that day’s New York Tribune.

When he retired, Daniels wanted to be remembered for something other than his swimming. Along with his wife, Daniels founded Tarnedge Foxes, the oldest silver fox ranch in the U.S. Daniels was also an avid hunter, finding game in Mexico and on African safaris. He filled an entire trophy room in his mansion with huge animal heads, including rhinoceros and water buffalo.

To this day, several original buildings remain on the property, which is now a wilderness camp for the Boy Scouts. The mansion was torn down in 1973. The animal heads still hang in a big red barn.

Daniels moved to California in 1943, where he made headlines working as a swim instructor for the Army during World War II. He disappeared from the swimming world for a number of years. When he was inducted into the first class of the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1965, no one knew where he was. Daniels resurfaced in 1972, but had gone nearly blind. He died the next year in Carmel Valley Village, California.

“There seem to be rhythm and music and poetry in his swimming,” wrote the San Francisco Call in 1911. The quote was describing Daniels, but anyone who remembers Phelps barreling down his lane in Beijing or London or Rio de Janiero could say the same. Perhaps in Phelps, we see that a part of Daniels still lives on. That, through the beat of his flutter kick, he simply became music.

Before Michael Phelps, There Was Charles Daniels

Comments