Author: Allison Quady Arts Editor

On Thursday, Nov. 1, Scott Atherton, Wonnacott Commons faculty co-chair and organizer of the three-day Iranian Cinema and Culture Symposium, announced the purpose of the Symposium: "To bring the culture of Iran more to the foray at Middlebury College from as apolitical and as nonreligious a perspective as possible."

Leger Grindon, professor of film/video, introduced the two speakers to follow, and the keynote address began with "Cinema, Politics and Society in the Islamic Republic of Iran," presented by Negin Nabavi, assistant professor of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. Her discourse on the preceding decades of Iranian cinema emphasized that in the '90s Iranian cinema became one of "the most vibrant and prolific cinemas in the world." Cinema is a helpful thing for the image of post-republic Iran whose contemporary politics waver over how liberal or conservative an Islamic Republic should be.

According to Nabavi, as a medium, cinema effectively brings out the paradoxes and contradictions found in Iran. Contrary to American cinema and the cinema of much of the world, you will not find action films, romantic comedies or the type of blockbuster movie that is created around the popularity of a movie star in Iranian cinema.

Instead, Iranian cinema finds stars in the younger generation, using children to express poetry and innocence and to circumnavigate the government censors. Using children is incredibly pragmatic because of the loopholes in the regulations regarding their portrayal onstage. With the many restrictions on violence and love between men and women, directors have turned to children as a means of expressing societal themes.

Since the Islamic Revolution and the overthrow of the Shah in 1978-79, the censors have become highly restrictive and filmmakers have responded to the challenge of making movies in greater numbers and with a greater passion than before. After the revolution, all things western were condemned because of their association with the Shaw and cinema fell into this category. Nabavi stated that 180 cinemas were set on fire and destroyed nationwide. Nabavi continued to say, however, that in 1980 a new revolutionary elite came to power and opened the door declaring that cinemas were no longer forbidden, but that they had been misused by the former regime. Films respecting the government codified regulations and approved of content by the censors were allowed.

Amongst the government regulations was the ambiguous place of women in front of the camera. The portrayal of women was left unclear, causing much anxiety about casting women. At first they were not cast at all and with time they were cast in the background in inactive parts often shown seated so as not to distract the men with their presence.

Ironically, Iranian women today are a major presence on screen and behind the camera. There are currently 62 active women filmmakers in Iran now, whereas at the time of the revolution there was one. Nabavi stressed that, "In spite of the restrictions about women, the constraints have come to represent a challenge and an invitation to push the barriers." The Iranian audience consistently supports films of controversial subjects.

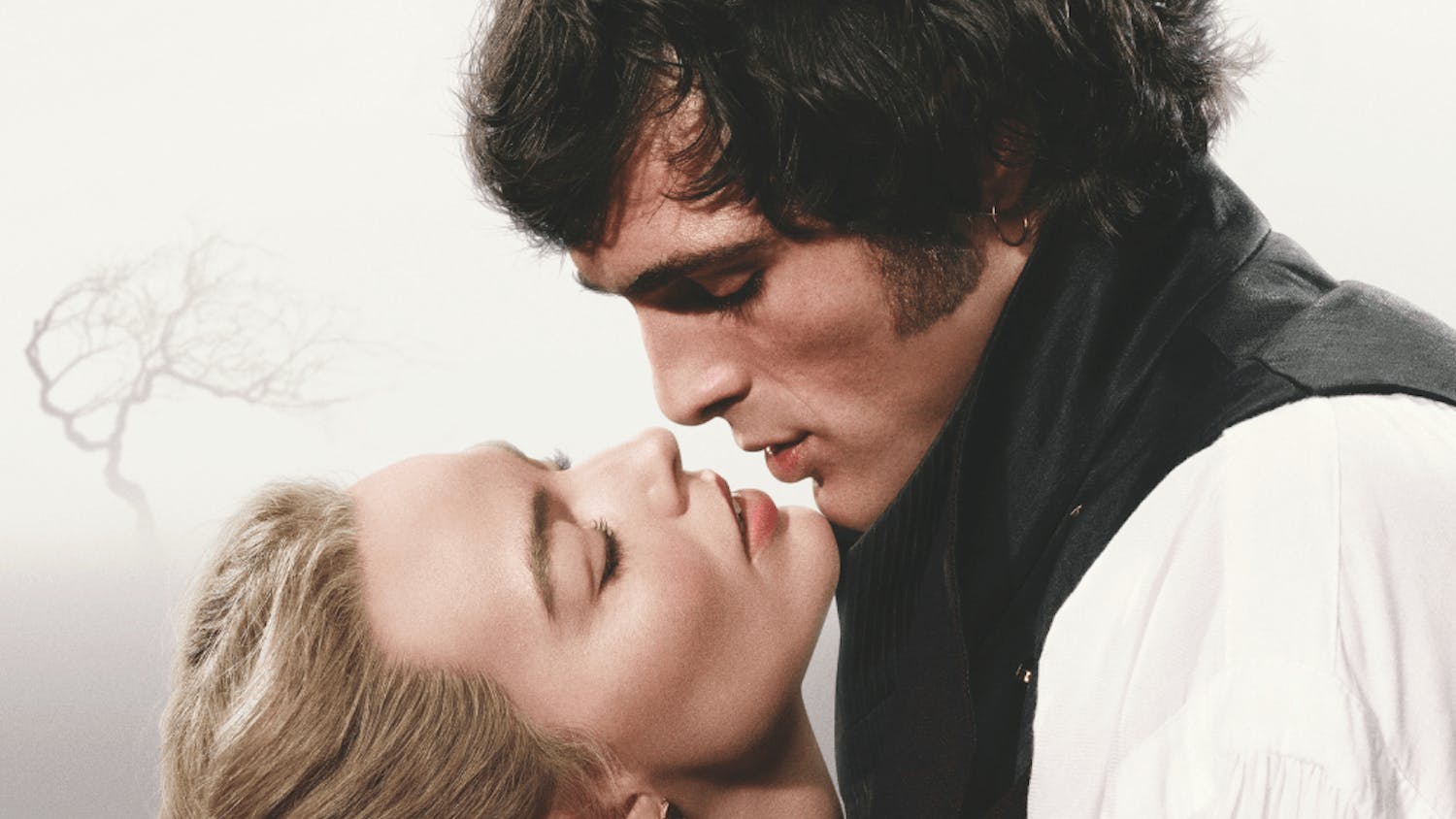

Throughout the film, subtle symbolism is imparted to the audience. Nabavi demonstrated this symbolism with clips from two past Iranian films demonstrating ingenious tactics to circumvent the censors without sacrificing their subject. In the first film it was understood that a man and a woman had fallen in love merely through the close up camera shot on the woman's face upon saying hello and goodbye to her lover. The film was the story of a love triangle, the irony being that the two women depended on the man for societal reasons although they possessed all the strength of character that he lacked.

The second clip was another sort of triangle in which a woman's consent to her husband taking a second wife was expressed through the sharing of laughter and food.

The dialogue between the man and woman must be necessarily scarce or simple, but onscreen actions speak louder than words.

Nabavi ended by once again emphasizing the ironies of Iranian cinema and the many tabooed subjects including suicide, murder, unemployment and mental disease that had been broached through innovative methods of circumnavigating the censors.

Critic Unveils Subtleties of Iranian Cinema

Comments